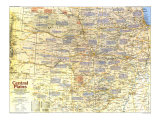

* Lesson plan idea - have your students update the information and latest statistics concerning the Central Plains states; discuss, contrast and compare the political, economic, and environmental situations the region is dealing with currently. • maps

IN THE EARLY 1820s Maj. Stephen H. Long named the Great American Desert and thus misjudged much of the Central Plains, home to Indian horsemen and buffalo and probed by the Spanish nearly 300 years before. Progressively drier to the west, but not a desert, the region was a sea of grasses. Tall prairie grass cloaked much of the east, giving way to the shortgrass.

With French fur trappers moving toward the Central Plains – claimed by France as part of Louisiana but also claimed by Spain and England – Spain planted toeholds in east Texas in the late 1600s. The French founded St. Genevieve in the 1730s, but in 1762 Louisiana went to the Spanish. In 1803 the U.S. purchased Louisiana, recently returned to France, and dispatched military explorers.

President Andrew Jackson abetted hunger for Indian land. In 1830 he signed the Indian Removal Act, and eastern tribes were directed to the as-yet-unwanted plains. Buffered by Army posts along a supposedly permanent Indian frontier, settlers spilled into the new states of Missouri (1821) and Arkansas (1836).

Like a magnet the West drew wagon trains across the unfamiliar plains, protected by the Army along several routes. By the 1870s many tribes had signed treaties forcing their removal to Indian Territory. Land seekers continued flowing into Kansas, which joined the Union in 1861, and streamed into Nebraska after statehood in 1867.

As fast as buffalo fell, people flocked to the plains, and in 1890 the census reproted that “there can hardly be said to be a frontier line.” Railroads underpinned the open-range cattle kingdom, then undermined it by pulling in farmers. Armed with steel plows and iron wills, with barbed wire and windmills, grangers and nesters fenced the range. By 1907, when oil-rich Oklahoma became a state, bountiful corn-and-livestock and wheat belts spanned the Central Plains. Railroads also concentrated industries and spurred lead and zinc mining.

With mechanization, farms grew in size but shrank in labor force, and today three-fourths of the population is urban. Aquifer-depleting center-pivot irrigation raises crop yields, and genetic engineering promises still greater returns, though droughts can wreak havoc, and the vagaries of politics and economics can turn yesterday's gain into today's foreclosure. Yet farmers have made a granary out of the dry plains, which the Long expedition had deemed “almost wholly unfit for cultivation.”

1. 1540-1807 - INDIANS AND ENTRYWAYS - BY THE mid-1600s – a century after Spanish explorer Francisco Vasquez de Coronado reached fabled Quivira – nomadic Apaches had acquired Spanish horses, beginning their spread from Mexico. By the late 1700s the horse culture had been adopted throughout the Central Plains, by nomadic buffalo hunters, such as the Kiowa, and by horticultural villagers, such as the Pawnee, who made forays to buffalo-rich grasslands.

The horse intensified nomadism and, with firearms and trade with whites, transformed life. A new measure of wealth, it ensured more food, but as the prize of raiding parties and the bearer of hunters to contested buffalo grounds, it ignited conflict and kept the region in constant flux.

MOUNTED BUFFALO INDIANS - The use of the horse endowed the Arapeho, Kiowa, Kiowa-Apache, Cheyenne, and Comanche – tribes whose linguistic and cultural differences bespeak diverse geographic origins – with a very similar way of life. As mounted buffalo hunters, they came to represent the quintessential North American Indian.

SMALLPOX SCOURGE - In 1780, a smallpox epidemic swept across the plains from San Antonio, Texas, killing tens of thousands of Indians, one of many deadly outbreaks of the disease.

2. 1803-1845 - INDIAN LAND-WHITE LAND - LANDS CEDED by Great Plains border tribes, including almost 100 million acres by the Kansa oand Osage in 1825, would accommodate 70,000 eastern Indians in reservations. Instrument of U.S. policy, the Army built forts to safeguard westward passageways – the Missouri River, plied by fur trappers, the Santa Fe Trail, used by traders after 1821, and the Oregon Trail.

Anglo-American farmers and planters from the South, including many Scotch-Irish, snapped up Mississippi-Missouri and Arkansas River bottomlands; many Germans chose the malaria-free bluffs and Ozark Plateau. By 1845 settlement was widespread, and St. Louis was the gateway to the Central Plains.

CIVILIANS ON THE PLAINS - Military presence secured the way for traders, missionaries, and government agents who were even less successful at making farmers out of Indians than the missionaries were in Christianizing them.

3. 1845-1870 - THE GREAT ASSAULT - BY MID-CENTURY as many as 55,000 westward trekkers a year were breaching the Indian frontier. Reports by Army explorers and, after 1853, surveys for the transcontinental railroad also demystified the plains, Settlers, now at the borders of Iowa and Missouri, were clamoring for more land.

Even before the creation of Kansas and Nebraska Territories in 1854 doomed the “permanent” Indian country, squatters and townsite speculators had begun crossing the Missouri. The population of Kansas Territory soared from fewer than 10,000 in 1855 to nearly 110,000 in 1860, although these were bitter years for “bleeding Kansas,” torn by the issue of slavery. In 1862 the Homestead Act granted 160-acre farm sites for a filing fee, Despite the Civil War the rush into the state continued.

In 1865 an East Coast newspaperman described the soil around Fort Kearny, Nebraska, as “fat indeed compared to your New England pine plains.” Improved communications enabled massive westward expansion. Nebraska's population rose 424 percent, to 123,000, in the decade before 1870. Settlement began snaking up the Platte Valley, where the Union Pacific Railroad was selling land.

Increasingly, newcomers were foreign-born. Iowa contained 17,000 Norwegians; Czechs, seeking political and religious freedom, clustered in eastern Nebraska. Homesteaders still shunned the western plains, marginal for farming beyond the 98th meridian.

WHITE GAIN, INDIAN LOSS - Treaties with the Plains Indians in 1851 and 1853 offered pioneers unimpeded travel and the government the right to build roads and posts. Between March and June 1854, commissioner of Indian Affairs George Manypenny struck treaties with a dozen tribes in eastern Kansas and Nebraska that deprived them of almost 18 out of just over 19 million acres.

MISSOURI RIVER TRAFFIC - Keelboats, powered by wind, oar, pole, or tow rope, supplied Indian agencies and Army forts in the Northwest, returning laden with furs and hides. Shallow-draft steamboats ruled the upper Missouri in the 1860s but lost steam to the railroads. Bypassed river towns, such as Arrow Rock, declined.

CATTLE ON THE PLAINS - As Indians and buffalo receded, cattlemen established themselves on the plains. Railheads such as Abilene, Kansas, became the destinations of cattle-trail drives from Texas; the spread of farming forced these long drives father and farther west. Fenced ranches eventually replaced the open range.

OZARK HIGHLANDS - In the 1840s and 1850s stock raisers, mostly from the Appalachian hills of Tennessee and kentucky, cleared plots in the rugged, heavily wooded Ozark Highlands. After the Civil War, homsteaders arrived from northern states, and Germand immigrants grew wheat from elongated villages, or Strassendorfer.

ADVANCE MILITARY POSTS - The forward depot of Fort Leavenworth supplied advance posts, such as Forts Kearny, Dodge, and Riley, some of which, as markets, attracted civilian settlement. The Army built a network of roads and experimented with farming at its forts.

BUFFALO INDIANS - Nomadic western tribes dependent on the fast-disappearing buffalo resisted whites agressively in the 1860s. The Medicine Lodge Treaties in 1867 stipulated the relocation to Indian Territory of the Kiowa, Comanche, and southern Cheyenne and Arapaho, which was achieved only ater military action under Sheridan, Miles, and Custer.

DESTRUCTION OF THE BUFFALO - “When shooting at buffaloes on the parade ground be careful not to fire in the direction of the commanding Officer's quarters,” advised an order at Fort Riley. Railroads enabled the commercial slaughter of buffalo, officially encouraged as a way of subjugating Plains Indians. In 1871 more than four million animals were killed, most for their hides. Divided into two main herds along the thoroughfare created by the transcontinental railroad in 1869, the buffalo were all but annihilated during the next decade.

“BLEEDING KANSAS” - The slave-state/free-state question found tragic expression in Kansas following the 1854 territorial act, which left it to the Kansasns themselves to choose. The minority proslavery faction declared Lecompton capital, while the free staters picked Topeka. Blood was shed in Lawrence and elsewhere. Kansas entered the Union a free state in 1861.

4. 1870-1907 - LAST FRONTIERS - TIDAL WAVES of immigrants, highest in the 1880s, left pools of mostly northwestern Europeans; Germans, Scandinavians, irish, English, Scots, and Welsh. Among the floods of German speakers, Catholics from Russia's Volg region flowed out from Topeka, while Protestants from the Black Sea dispersed from Lincoln. Germans and Scandinavians preferred farming; the Irish and British gravitated to towns. Many Texans and Southerners claimed range rights in cattle coutnry.

Droughts in the the early 1890s drove out thousands of corn growers. Homesteaders turned to red winter wheat, especially the drought-resistant variety grown by German Mennonites from the steppes of the Ukranine. Farmers also began irrigating.

BLACK MIGRATION TO KANSAS - Land and hope for true liberty lured thousands of blacks, some called “Exodusters,” to Kansas – where Nicodemus was their best-known town – from Kentucky, Tennessee, and elsewhere in the Deep South after the mid-1870s.

WISHFUL RAINMAKING - Boosterism, climatic ignorance, good rainfall years, and wishful thinking led many homesteaders to believe that “rain follows the plow.” Droughts eventually cooked that notion and forced more rational responses, such as dry farming, practiced west of the 98th meridian, to conserve soil moisture.

5. 1900-PRESENT - AGRICULTURAL HEARTLAND - WHEN GRAIN demand was high, as in the World Wars, “suitcase,” or absentee, farmers planted in marginal areas. National grasslands in the 1930s helped limit the High Plains plow-up, and the 1950s Conservation Reserve Program also substituted grass for grain. Irrigation made Nebraska's sugar beet industry, nurtured by German-Russians, then worked by migrant Mexican-Americans, second only to Colorado's in the 1930s.

Highways reemphasied the region's historic role as passageway between East and West and encouraged tourist to discover the Ozarks. Traditional metropolitan hubs have dropped, but local agribusiness and light manufacturing centers, such as Hutchinson, Kansas, continue to bloom.

SPARSE POPULATION - Vast areas of the Central Plains remain relatively empty. With 7.3 million people, Kansas, Nebraska, and Oklahoma contain only 3 percent of the nation's total population. Oklahoma's Indian population of 169,000, however, ranks second, below California's.

PETROLEUM WEALTH - Estimates of reserves give Oklahoma 931 million barrels of oil and 17.3 trillion cubic feet of natural gas; Kansas is thought to have 344 million barrels and 10.2 trillion cubic feet.

FARMING PATTERNS - Single crops – drought-hardy sorghums, soil-building alfalfa, and since World War II soybeans – have gained ground on increasingly large, capital-intensive farms. For corn and wheat growers who practice fallowing, those east of the 98th meriian often plow under grass or clover, and those to the west replenish soil with crop waste.