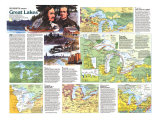

The 1973 Wisconsin, Michigan, and the Great Lakes: Land Between the Waters map features:

• An introduction to the region

• Insets of the Detroit and St. Clair Rivers, St. Mary's River, and the Welland Canal

• An illustration of the Great Lakes showing their individual sizes, depths, and volumes

• Articles and tips for travelers

Wisconsin, Michigan

* Lesson plan idea - have your students update the information and latest statistics concerning the Great Lakes of the United States; discuss, contrast and compare the political, economic (employment), and environmental (climate change) situations the Great Lakes region is dealing with currently. • maps

Land Between the Waters map text -

Newcomers to Wisconsin, Michigan, and the Great Lakes have been uncovering pleasures and surprises ever since French explorer Jean Nicolet paddled into this region in 1634. On a search for a northwest passage, he stepped ashore near Green Bay, thinking he had reached the Orient.

In damask robes, he presented himself to a people he took for Chinese. Actually he had met the Winnebago, a trive of farmers and hunters who called themselves “people of the real speech.” His discoveries stimulated the exploration – of a prodigious empire. Though it lacked the spices and riches of the Orient, it abounded in pine forests, ore deposits, lakes and waterways, fish and wildlife, and a suprisingly varied terrain.

Lumber barons of the past century took out much of the timber; mining companies skimmed off the richest ore; overfishing and such pests as the sea lamprey and alewife reduced the fish supply. But a bountiful land remains. Vacationists come from afar, drawn by the outdoors and north woods peace.

Yet the area also hums with business and industry – a bonus for the visitor who seeks more than recreation and quiet. You can watch automobiles being assembled in Detroit, Pontiac, and Lansing; buy baskets of cherries, apples, pears, and peaches at orchards lining Michigan's western shore; tour Milwaukee's breweries, nibble your way through cheese factories and shops of Wisconsin's dairyland.

Spring, summer, and fall prove the most enchanting times for visits, but increasingly the snowy winters fetch vacationists. By snowmobile or on skis, you can follow lake-to-lake trails. You can slide down a hillside or chance the harrowing run of a ski jump–legacy from Scandinavian immigrants. Even in his damask-robed imaginings, Nicolet hardly could have envisioned such sport.

GREAT LAKES -

How can you comprehend the size and import of the Great Lakes? Facts and figures merely begin to tell the story: Three of the five lakes– Superior, Huron, and Michigan– rank second, fifith, and sixth among the Earth's ten largest. With smaller Ontario and Erie, their combined area is 94,250 square miles; only the salty Caspian Sea, a lake of 143,550 square miles, has a greater expanse. From the eastern edge of Ontario to the western tip of Superior, the Great Lakes stretch a third the distance across the continent's middle. More than 25 percent of the United States' income from farming, mining, and manufacturing is earned in the Great Lakes region.

One way to plumb the size and appeal of the lkes is to embark by boat. Thousands do. Private pleasure craft swarm amid the fleets of low, flat ore carriers and fishing boats. Small ferries call at various islands spotted on these inalnd seas. You can also cross Lake Michigan on huge car-carrying vessels fitted with staterooms for overnight journeys.

Three or four centuries ago the only boats on the lakes were birchbark canoes, developed by the Indians and refined by French voyageurs. The canoe, as vital as the covered wagon in settling America, helped to open great reaches of the nation. Steamboats proliferated after completion of the Erie Canal in 1825; the flow of settlers via the canal and the lakes helped populate such cities as Detroit and Milwaukee. Often, however, the ships fell victim to exploding boilers, storms, or other disasters.

White-winged schooners ruled the lakes in the latter part of the 19th century, carrying coal, ore, grain, and lumber. By 1890 the traditional Great Lakes ore carrier had evolved, a forerunner of the behemoths that crawl across the horizon today. When the St. Lawrence Seaway opened in 1959, deep-draft ocean freighters put such places as Green Bay and Duluth-Superior within a hold's distance of foreign ports.

Vessels large an small pass through a network of canals and waterways that would puzzle those long-ago masters of the birchbark canoe, who simply picked up their craft and portaged when an impasse loomed. From the Superior end of the lakes, boats bypass rapids of the St. Marys River at the five locks of the Soo Canals. They glide from Huron to Lake Erie via the St. Clair River, Lake St. Clair, and the Detroit River. Then they shuttle from Erie to Ontario on the Welland Canal, who eight locks conquered the Niagara escarpment. From there the St. Lawrence River leads out to sea.

True tides measure only inches throughtout the Great lakes, but seiches–comparable to water sloshing back and forth in a tub–can change the water level several feet. When storms blow up–worst in autumn and winter– winds of 100 miles per hour or more can sweep across the lakes and create towering waves. Ice blocks many harbors and channels in winter, and major shipping activity has usually ceased from mid-December to April. But withthe help of durable icebreakers, the navigation season is being extended.

Commercial fishing no longer flourishes as it did on the Great lakes a century ago. The mammoth sturgeon has nearly disappeared, and the whitefish and lake trout have decreased in number. But sport fishermen – especially in Michigan – get new thrills from the coho and chinook salmon that have introduced in the lakes. These former seagoing Pacific coast natives have adapted to a freshwater cycle, growing to scrappy 30- and 50-pounders in the lakes and migrating up mother streams in the fall to spawn and die.

In the heart of the nation, a thousand miles from the nearest ocean, vacationists can retreat to lake-washed islands that seem as isolated as Pacific atolls. Isle Royale National Park lies in Lake Superior, 50 miles off Michigan's Upper Peninsula and accessible only by boat or floatplane. Visitors can come and go only between mid-May and mid-October. Even then they scaredly disrupt the rocky, wooded wilderness, which has no roads and almost no signs of commerce. From one end to the other, Isle Royle is coursed only by hiking trails (more than 160 miles) and the paths of moose and wolf. Overnight visitors can stay at either of two inns perched on opposite ends of the island, or hike to any of 24 campgrounds.

Closer to the mainland but almost as primitive are the Apostle Islands, which cluster at the northern tip of Wisconsin. Madeline draws travelers by boat and plane; the score of other Apostles – some wild and uninhabited – are protected as part of a national lakeshore.

Beaver Island, Lake Michigan's largest, was once a Mormon stronghold, later a fishing outpost of Irish settlers. Roughhewn and uncommercial, Beaver slowly develops its tourist potential. By contrast, Mackinac Island – clipped, cultured, and commercial – has attracted visitors since Indian days. The little two-by-three mile island, which lies in the Straits of Mackinac hard by the “Big Mac” bridge, depends on tourism for its livelihood, but does so with charm and taste. It forbids auto traffic and keeps its wooded profile spotless. Visitors get round as natives do – by foot, bicycle, horse, or carriage.

The chain of islands stretching into Lake Huron from the St. Marys River – Sugar, Neebish, St. Joseph, Drummond, Cockburn, Manitoulin – once served as fur-trading encampments and as fueling stations for wood-burning steamboats. Though caught in the modern pace of lake activities, they have retained a primeval air the Indians felt when they paddled by centuries ago.

WISCONSIN - constantly temps the visitor to slow his pace, turn off the main highway, and follow the first back road into the countryside. The state's network of secondary roads, built so farmers can get to market easily, benefits bicyclist as well as mortorist. The state even has laid out an extensive series of bicycle routes that follow quiet roads in the southern half of the state.

If you've the time and energy, you can pedal across Wisconsin on the 300-mile bikeway from La Crosse to Kenosha, a route that winds through picturesque river valleys, dairyland, and lake country. From Sparta to Elroy you leave the highway to cycle 32 miles on a century-old railroad bed – resurfaced with gravel and complete with three tunnels.

Southern Wisconsin, generally hilly, bucolic, and green, is the center of the richest dairy belt in the nation, while northern Wisconsin runs more to forestland and lakes. Many of the small farm communities still retain the flavor and customs of the European immigrants– Swiss, German, Scandinavian, Cornish – who settled in the last century. A visitor clinging to back roads and small towns can't help but feel he is slicing into a corner of northern Europe.

New Glarus, for example, seems to have been lifted straight out of Switzerland. Swiss founded the town in the 1840s; the architecture still bears an Alpine imprint, restaurants serve Kaseschnitte (a hot open-faced cheese sandwich), a factory turns out Swiss lace, and townsfolk commemorate Heidi and William Tell in annual events.

German-Americans have stamped their traditions on numerous towns throughout the state. Fleeing oppression in the 1800s, the Germans brought to Milwaukee their cultrual interests, beer-making prowess, and ideas of city government. La Crosse has an annual Otoberfest echoing Munich's.

Norwegians settled in Stoughton and Mount Horeb, near Madison. Scandinavian names stand out on shops and mailboxes. The Norwegian flag and its colors decorate storefronts and tidy homes. Each May, Stoughton dresses itself up in Old World costumes to celebrated the Norwegian Independence Day.

Mineral Point, southwest of madison, was settled in the 1830s by Cornish immigrants who came to work local lead deposits. Earlier miners had lived there in caves and mine excavations, their badgerlike existence– and not the burrowing animal– gave Wisconsin its nickname of the Badger State. The Cornish built sturdy homes; stone houses march in quaint row on Shake Rag Street – its name stemming from a time when wives stood at front doors and shook rags to signal hubands home for dinner. They served them pasties – pies filled with meat and vegetables. You can eat these and other Cornish specialties at local restaurants.

Most of Wisconsin once was ground by glaciers, but the southwest corner escaped the icy advances and retreat. This it boasts a hilly profile unlike the terrain elsewhere. Here one of Wisconsin's loveliest drives follows the Mississippi river, whose valley cuts a broad path between painted bluffs as it meanders from la Crosse to Prairie du Chien.

At Wisconsin Dells the Wisconsin River cuts through a spectacular seven-mile gorge. By tour boat or canoe you can glide past biarre stone formations in the sheer cliffs.

One of Wisconsin's leading vacation spots is the Door Peninsula, a 70-mile-long finger of land that juts into Lake Michigan. Door's low-key resorts, shining weatehr, and cherry and apple orchards draw tides of visitors. Many call the area the “inland Cape Cod.” The peninsula got its name from French explorers who labeled it Porte des Morts– Door of the Dead – for the battering waves that drove dozens of ships to the bottom. Scuba divers come in summer to hunt for remains of the more than 200 charted shipwrecks. French explorer La Salle's bark the Griffon – first sailing vessel to ply the lakes above Niagrara – coursed these shores on a fatal voyage; some believe it sank in Lake Huron.

Wisconsin's northern half is dotted with broad tracts of national and state forest. Rhinelander and Hayward, once logging camps, are now centers for resort districts. Hayward each July stages a lumberjack contest.

MICHIGAN divides rather neatly into three parts –the Upper Peninsula and the southern and northern halves of the Lower Peninsula. Geography, industry, and tempo of life are markedly different in each.

Across the southern half of the Lower Peninsulas cluster Michigan's big cities and factories and fields that turn out most of her products. Detroit, home and working place for 1,500,000 people–the nation's fifth largest city–is Motor City, U.S.A. Oldest metropolis in the Midwest, Detroit was established in 1701 as a fortress and fur-trading post. Near the end of the 19th century it had grown to a tree-shaded center of 200,000 making beer, carriages, furniture, stoves. Then some men named Ford, Olds, and Buick began to tinker with putting engines into carriages. The place has never been the same.

Today Detroit has more than 100 automobile factories (remember, this is the 1973 data stats), perhaps none so impressive as Ford's Rouge Plant in adjoining Dearborn. Visitors to this 1,200-acre beehive can watch cars being assembled on a 1,160-foot line, emerging at the rate of nearly one a minute. Frequent weekday tours leave from the plant's nearby Visitor Reception Center.

Dearborn also is the site of the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village, two remarkable monuments to American ingenuity and culture developed by Henry Ford himself. Among the structures Ford collected and preserved in Greenfield Village are the homes of Noah Webster, Luther Burbank, and the Wright brothers. You can also view the shed where Ford built his first car, and vsit the laboratory in which Edison developed the incandescent lamp.

Southern Michigan–despite Detroit, Flint, Grand Rapids, Lansing, Battle Creek, and Kalamazoo – is not entirely given to industry. Away from urban centers you pass through pleasnt fields remindful of Europe's Low countries. in fact, in sprintime, when tulips and other flowers blossom around the city of Holland, you might as well be on the IJssel Meer. Holland has staged a tulip festival each year for nearly half a century. All year round you can visit the city's two wooden-shoe factories, or climb to the opt of an old windmill brought over from North Brabant.

North of Holland and Musegon in the west and Flint and Saginaw in the east, you leave behind Michigan's industrial region and enter an area of forests, lakes, and small towns. The scenic beauty and a delightful climate – discovered in the 1800s to be remarkably pollen free –early drew vacationists. A resort industry still flourishes.

Visitors flock to Charlevoix, Petoskey, Mackinac Island, Traverse City, and other spots, In may the cherry-growing district around Traverse City turns white with blossoms; a variety of cherry desserts are served all year in area cafes.

Ernest Hemingway spent some 20 summers at the family cottage on Walloon Lake near Petoskey, and many of his early stories are set in the area. With autumn comes a blazing display of foliage.

Northbound motorists can follow U.S. 27 and Interstate 75 up the middle of the Lower Peninsula – or take either of the more leisurely eye-filling routes: U.S. 23 north from Saginaw Bay along Lake Huron, or U.S. 31 on the western, Lake Michigan, side. Near Glen Lake – placid, wooded, and ranked among the nation's loveliest –stands a geologic attraction name Sleeping Bear Dune. This 600-acre mountain of sand rises more than 400 feet above Lake Michigan. On the dune you can see bleached remnants of trees buried hundreds of years ago by wind-driven particles, and subsequently re-exposed. You can climb to the sandy heights by foot, or ride a sight-seeing dunesmobile.

At the northern end of the Lower Peninsula all roads converge in a soaring leap over the Straits of Mackinac by the gleaming bridge they call “Big Mac.” Completed in 1957, the 100-million-dollar bridge stretches five miles. It links Mackinaw City with St. Ignace in the Upper Peninsula, and with Canada at the end of Interstate 75. In span between main towers, only New York's Verrazano-Narrows Bridge and San Francisco's Golden Gate are longer. Automobiles are assessed a $1.50 fare. (2012 data- $2.00 per axle for passenger vehicles ($4.00 per car). $5.00 per axle for motor homes, and commercial vehicles.)

Crossing “Big Mac,” you enter Michigan's third distinct region, the Upper Peninsula (or U.P., as residents call it.) Once its residents identified more closely with neighboring Wisconsin than with downstate Michigan, but since the advent of the bridge, they tie increasingly to the busy lower section.

Still, the U.P.'s tip around Houghton and Hancock seems eons and cultrues removed from Lansing, the stae captial. Finnis immigrants gave the area an unmistakable flavor; Hancock's Suomi College exports it with a noted touring choir. Copper – mined thousands of years before the birth of Christ by a mystery-shrouded group of Indians – formerly underpinned that area's economy. Now Houghton and Hancock serve as centers of a burgeoning vacation industry.

From east to west the rugged Upper Peninsula extends 320 miles, edging lake shores with jagged outline. One of the most attractive stretches of coast lies along Superior northeast of Munising. Cruises from town take you past 15 miles of erosion-carved and multicolored sandstone cliffs– the Pictured Rocks held in awe by Indians as a home of gods and spirits. Farther along the coast a 12-mile beach of sand and pebbles attracts hikers, photographers, sunbathers,and the hardiest of swimmers. superior, coldest of the Great Lakes, seldom warms to more than 60ºF. The beach and cliff areas are protected in a national lakeshore.

The U.P. has only one express highway – an extension of Interstate 75 – but speed in this unhurried land is not essential. You need time and patience tp appreciate the lonely wilderness, the mine sites, the ski slopes, and the lakes and waterfalls of this isolated region.