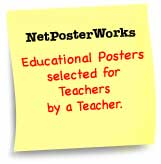

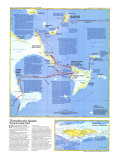

NUMEROUS islands in the western Atlantic have been named as Columbus's first landfall. the question of which is correct has aroused controversy for two centuries, with Watling Island, renamed San Salvador, the choice of many scholars. And if one lays down the daily courses and distances given in the Columbus log, taking no account of current or leeway (the downwind skid of a vessel); the track does lead to Watling.

But it is impossible for anything floating in the sea – a bottle, the Santa Maria, or the Queen Elizabeth II – to escape the influence of current, so if the Columbus track is retraced with allowance for current and leeway, the end point falls some 60 nautical miles, a full degree of latitude, to the south of Watling.

No one had ever traced such a track, as a modern navigator would do it, until Luis and Ethel Marden laid down the one shown in the map. Using daily plotting sheets, trigonometry, and small navigation computers, they plotted the fixes for each day's run. Beginning at Columbus's starting point off Gomera in the Canary Islands, the map's black line follows a no-current course, the red line, a course adjusted for current and leeway.

Columbus logged his distances from dawn to dawn in leagues, but what does that mean in modern measure? Most scholars have used 3.18 nautical miles for the Spanish sea league, but navigation authority Dale Dunlap found a 16th-century manual that unequivocally defines the Spanish marine league as 2.82 nautical miles. Later the Mardens found an identical definition in an even earlier manual, published within 68 years of Columbus's death.

Currents of 1492 are unknown, but the Earth's physiography has changed little in 500 years, an eye blink of geologic time. Currents shown are taken from monthly United States pilot charts, based on data collected for 150 years. Given the ships' course and distance, with the current's set (direction of flow) and drift (speed), a vector plotting for trigonometric computation gives the position at the end of each day's run ... .

Naval architect Alan Pape estimates that Columbus's shallow-draft ships would make 1.5º of leeway on a westward course in the northeast trades, where the wind is over the helmsman's right shoulder. Leeway was reckoned as far as 40º west longitude, where winds became evenly divided on the stern until just before landfall.

Wind roses along the course indicate prevailing northeast trades that begin near the Madeira Islands and inexorably carried the Columbus flotilla to the Bahamas. Probable compass variation for 1500 is based on a Dutch study published years ago but still the best available. As the track cut isogonic lines, compass headings in the log were converted to true courses.

Columbus landed on October 12, 1492, according to the Julian calendar. In modern Gregorian reckoning nine days must be added, so Columbus Day should really be celebrated on October 21. When the Mardens consulted the pilot charts in their plotting of the Admiral's track, they took this calendar differnce into account.

Columbus estimated his speed through the water with a seaman's accuracy, but he could not judge the direction and strength of the current, so a current-added track comes out too far west. Back-tracking along this course to the first sight of land–any land–gives the percentage of overrun.

It is evident that current pushed Columbus nine miles farther in every hundred than his estimate. Subtracting this from the daily logged runs and replotting the track brings us to the most probable position of landfall–Samana Cay.