* Lesson plan idea - have your students update the information and latest statistics concerning the Northern Plains of the United States; discuss, contrast and compare the political, economic (employment), and environmental (climate change) situations the Midwest region is dealing with currently. • maps

Northern Plains map text -

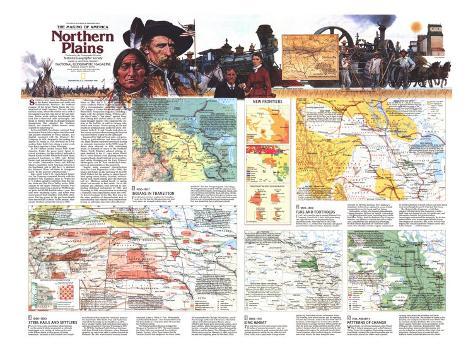

SWEEPING WEST from the Missouri River to the Rocky Mountains and north into Saskatchewan Province, the northern expanse of the Great Plains forms the very heartland of North America. This dry, almost treeless realm, where the winters are as cold as the summers are hot, was one of the last frontiers. Before white settlers transformed the land into a wheat and cattle cornucopia, vast herds of buffalo thrived on drought-resistant shortgrasses that stippled the Northern Plains, and nomadic Indian hunter rarely wanted for meat.

In the mid-1600s Frenchmen ventured from the forested Great Lakes region into lake-studded prairies inhabited by Sioux Indians. The English countered with the Hudson's Bay Company in 1670. Awarded a fur-trading monopoly by France in 1730, the Sieur de la Venrendrye later built forts along a water route from Lake Superior to Lake Winnipeg.

In 1763 Britain ousted France from North America. Under the peace treaty Spain received Louisiana, but the territory returned to French hands in 1800. When the United States purchased Louisiana in 1803, only British traders had intensively exploited the region's fur wealth. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark's expedition fired American interest in the Northwest, and in 1809 the U.S. declared the Missouri River off-limits to foreigners lured “for the purpose of Indian trade.”

John Jacob Astor's St. Louis-based American Fur Company competed fiercely with the Hudson's Bay Company. When the U.S. traders agreed to withdraw from the border lakes and Red River Valley in the 1830s, Indians in the upper Missouri country were supplying Americans as many as 25,000 muskrat pelts and 50,000 buffalo robes a year. But furs were becoming scarce, and tribes were under assault from smallpox and white settlements. Having grown in the previous decade from fewer than 10,000 to 70,000 people, Minnesota Territory joined the Union in 1858.

Following a bloody uprising by the eastern Sioux in 1862, the U.S. Army strung forts across northern Dakota Territory. In 1874 a reconnaissance expedition under Lt. Col. George A. Custer discovered gold in the Black Hills. Prospectors surged in, violating a treaty with the western Sioux. Within a decade after Custer's “last stand” against Sioux chief Sitting Bull and his allies in 1876, railroads brought hunters who hastened the demise of the buffalo, as well as farmers who fueled land booms. Towns spring to life and swaths of farmland came under the plow. Settlement in the U.S. and Canada took place under survey systems whose rectangular imprint soon etched widely on the landscape.

Squeezed by high railroad rates and price-fixing by grain-elevator and flour-mill owners, many farmers suffered foreclosure during an economic depression in 1890. Boom days returned in 1898, enthroning wheat as monarch of much of the Northern Plains. North Dakota's railroad milage almost doubled in the 15 years before World War I, when farmers were planting wheat on marginal lands. Small railroad towns proliferated, while Winnipeg and the Twin Cities of Minneapolis and St. Paul established themselves as metropolises of the grain belt.

Despite some economic diversification since the Great Depression of the 1930s, the region still banks on the soil. In 1985 North Dakota led the nation in production of hard spring wheat, barley, flaxseed, and sunflower seed. South Dakota grew the most oats and rye. Montana ranked fourth in spring wheat and seventh in beef cattle. Yet as the Dakotas and Montana look forward to celebrating statehood centennials in 1989, and Wyoming in 1990, many farmers are enduring a financial crisis-unparalled since the 1930s. To stay in business in the '80s, they draw on the same qualities of determination and resourcefulness that enabled their predecessors to turn an unbroken land into a breadbasket.

1. 1650-1807, INDIANS IN TRANSITION - THE FRENCH-CANADIAN explorer La Verendrye noted in 1738 that the Mandans not only had “corn, meat, fat, dressed buffalo robes, and bearskins” but also European goods. the village-dwelling Mandans traded with Cheyenne and other mounted nomads, bartering guns, beads, and corn for horses and buffalo meat and robes. By the early 1800s guns and horses had given Indians new strength and mobility, but the fur trade had snared them in a net of dependence on European goods that was desolating their traditional culture.

ENTRYWAYS TO THE NORTHERN PLAINS - By the 1700s French voyageurs were paddling canoes deep into the interior, where tribes trapped beaver, otter, and muskrat. One route took traders from Green Bay to the upper Mississippi River. More heavily traveled was the trunk canoe route from the fur depot of Grand Portage of Lake Winnipeg. From there Europeans pushed up the Saskatchewan River to the Peace River system and the Rocky Mountains. The Missouri River offered a third entryway.

RIVAL COMPANIES - Although the London-based Hudson's Bay Company established a trading beachhead at Cumberland House in 1774, the Montreal-based North West Company dominated the pivotal Winnipeg basin region until the 1790s. Bay Company expansion after 1793–especially along the Rainy, Assiniboine, and Red Rivers–sparked a flurry of fort and post building. Need for buffalo meat to make into pemmican drove traders beyond the forest to the eastern fringes of the grasslands.

2. 1807-1860 - FURS AND FOOTHOLDS - IN THE EARLY 1800s the newly formed Missouri Fur Company, based in St. Louis, built posts along the upper Missouri, but Blackfoot Indians obstructed trade. After the War of 1812 with Britain, the U.S. erected Fort Atkinson and signed peace treaties with area tribes. American traders returned. In 1831 the American Fur Company's steamboat, Yellowstone, ushered in an era of bulk transport between St. Louis and Fort Union.

Meanwhile, in 1811, the Scottish philanthropist Thomas Douglas, fifth earl of Selkirik had secured a 116,000-square-mile grant, including much of the Red River Valley, from the Hudson's Bay Company. Within a year Selkirk's colonists had sown wheat,corn, and potatoes near present-day Winnipeg. By mid-century hundreds of “Red River carts”– crude, two-sheeled, wooden wagons, most owned by metis trademen of mixed Indian and white blood were screeching between St. Paul and Fort Garry.

The Hudson's Bay company – which had merged with the North West company in 1821 – held sway over Rupert's Land, its charter area, and the western interior, but private traders increasingly undermined the monopoly. By the late 1850s farmers were clamoring for Britain to strip the company of its charter, lest, as the Toronto Star argued, the Canadian prairies “remain sacred on to the Indians ... and fur traders.”

PALLISER'S PREDICTIONS - In the 1850s Britain dispatched an expedition led by Capt. John Palliser to determine the agricultural potential of th Canadian plains. Palliser identified a “fertile belt” extending west of Lake Winnipeg. Farther south, in what would became known as Palliser's Triangle, he asserted that farming would be risky, thereby delaying settlement of a productive area.

SIOUX TRADE - the Teton Sioux benefited from their strategic location near the Missouri River, surrounged by the northern buffalo herd. At Fort Pierre, one of dozens of white trading posts between the Big Sioux River and the Black Hills, they exchanged furs and buffalo meat and robes for a bonanza of manufactured products.

EXPLORATION AND SURVEY - In the late 1830s the U.S. sent Jean N. Nicollet, a French scientist, to explore the Northern Plains. His enthusiastic reports about the prairies in the southeastern part of future North Dakota intensified popular interest in the area. In the early 1850s Isaac I. Stevens' government-sponsored survey of a northern route for the proposed transcontental railroad further demystified the still obscure region.

49TH PARALLEL - In a convention on October 20, 1818, Britain and the U.S. agreed that their mutual boundary should run westward “from the Lake of the Woods, along the forty-ninth parallel of north latitude” to the Rocky Mountains. the precise alignment of the boundary, however, was not settled until 1925.

3. 1860-1890 - STEEL RAILS AN SETTLERS - FEAR OF INDIANS and uncertainty about farming on the semiarid plains evaported as railroads leapfrogged west, setting off rushes such as the Great Dakota Boom at the expense of Indian homelands. Railroads at first boosted river freight to and from railhead ports but eventually replaced the steamboats. After the St. Paul and Pacific line entered Breckenridge on the Red River in 1871, heavy steamer traffic plied north from there until a railroad connected St. Paul and Winnipeg in 1878.

By 1873 the Northern Pacific Railway had been built from Duluth to the Missouri, where Bismarck sprouted up, and in the 1880s it reached beyond the Badlands. By 1889, when Dakota Territory earned statehood, James J. Hill's St. Paul, Minneapolis, and Manitoba Railroad – later renamed the Great Northern Railway – had more miles of track than the Northern Pacific.

The Dakota Southern Railway bridged the Missouri at Yankton in 1873. The town boomed, but Sioux Falls soon surpassed it as southern Dakota Territory's hub. Speculation that the Northern Pacific had designs on the lower James River prompted the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul to forge northward to Aberdeen. The fertile valleys of the Red and James Rivers, where Mitchell and Huron grew into major centers, drew many settlers, while towns such as De Smet were born in a scramble along the railroad between the Big Sioux and the James. The Chicago and North Western arrived at the Missouri in 1880, and Pierre became the freighting point for the Black Hills.

BONANZA RANCHING - As the Central Plains and Rocky Mountain states became overgrazed and railroads opened up the Northern Plains, Americans and Europeans–Britons chiefly–invested heavily in huge “bonanza” cattle ranches. Devastating winters in the late 1880s bankrupted many of these open-range operations in the Black Hills and Badlands and accelerated the shift.

LURE OF THE NORTHERN PLAINS - Between 1879 and 1880 Dakota Territory's population skyrocketed. Some newcomers bought tracts from railroads or the government, Large numbers–many of them foreigners–filed land claims under the Homestead Act of 1862 or the Timber Culture Law of 1873. Most American settlers came from midwestern states, where virgin land had become scarce.

RAILROAD LAND GRANTS - Government land grants provided incentive for railroad building. Under its 1864 charter the Northern Pacific was awarded 40,035,067 acres–more than any other U.S. railroad. In Dakota Territory alone it received nearly 11 million acres. The company had a 400-foot track right-of-way and alternate square-mile sections forming an 80-mile-wide checkerboard. If sections in these “primary limits” were considered unusable (swamp, for example), the railroad could make up the difference from 10-mile-wide strips called “indemnity limits.”

RECTANGULAR SURVEY - The federal Land Ordinance of 1785 was the basis of the Rectangular Survey, or Township and Range system, under which government surveyors platted townships on public lands from the Midwest to the Pacific Ocean. Each township covered 23,040 acres, subdivided into 36 sections of one square mile, or 640 acres. One or two sections were set aside to provide revenues for public schools. Under the Homestead Act the remaining land could be subdivided into farms of 160 acres, or a quarter section.

SCIENTIST-PIONEERS - Government surveyors charged with laying out new townships were the vanguard of settlement on the Northern Plains. Agents at federal land offices used surveyor's maps and field notes to direct buyers and claimants to suitable tracts. Yet so heavy was the influx to prime areas during the boom of the 1880s that systematic survey became impossible. Speculation, fraud, and tenancy often resulted.

REDUCTION OF SIOUX LANDS - In 1851 at Fort Laramie the Sioux signed a treaty assigning them to a reservation. in 1868 a new Fort Laramie treaty reduced the western part of the Great Sioux Reservation giving access from the east to Montana's gold mines. That treaty was abrogated in 1876, two years after the Custer expedition found gold in the Black Hills. The next year another was ratified. In 1889 Gen. George Crook, respected by the Sioux for his honesty, persuaded them to cede a further 11 million acres–half of what remained of the reservation.

4. 1890-1914 - KING WHEAT - THE NORTHERN PLAINS rarely receive more than 18 inches of rain of snowmelt a year, yet settlers found that in good seasons the dark soils yielded abundant wheat. By the 1880s the Red River Valley was a patchwork of huge wheat-producing busineses known as bonanza farms. Dry farming, new wheat strains, and the opening of lands by railroads, such as the line for Oslo to Kenmare, enabled growers to more than double North Dakota's acreage between 1898 and 1915. By then the state was producing three-fourths of the nation's durum wheat for macaroni products, and throughout the region the preferred bread wheat was a Canadian variety called Marquis. Cattlemen now ruled only in the most marginal areas.

LAST FRONTIERS - By 1915 the dry Missouri Plateau, stretching from the northwestern corner of North Dakota into estern Montana, had attracted many Norwegians and German-Russian farmers. South Dakota's West River region more than trebled in population between 1904 and 1913, when some four million acres of Sioux land were thrown open.

MIGRATION ACROSS THE BORDER - Thousands of Canadians. Ontarians mostly, immigrated to Northern Plains states during the economic doldrums of the late 1800s. Between 1907 and 1909 the Canadian government managed to entice more than 100,000 Americans –“the most desirable settler” – to Saskatchewan and Alberta. By World War I, half a million U.S.citizens had left for Canada's prairies.

ETHNIC MOSAIC - Throughout the region German-Russian, German, Ukrainian, Czech, and Hungarian immigrants tended to cluster in enclaves. Groups such as Hutterites and Mennonites – German-speaking sects – clung to their native language an religion. English, Irish, Canadians, and Scandinavia became assimilated more easily. In 1900 nearly four-fifths of North Dakotans were foreign born.

5. 1915 - PRESENT - PATTERNS OF CHANGE - WIESPREAD USE of farm machinery after World War I, federal programs such as the Missouri Valley Project for irrigation, fluctuation economic conditions – notably the Great Depression and the farm-credit crisis of the 1980s – and scientific farming have recast the economic and social character of the plains. The number of farms in the Dakotas, for example, has halved since World War II, but farm-size has doubled. The rural exodus, which caused both states to lose population in he 1930s and '60s, continues. But growth of light manufacturing, farm-product processing, and service industries in midsize cities helps stem out-migration. Distance from raw materials and markets limits industrialization on the plains.

FOSSIL FUELS - A BUMPER CROP - Exploitation of energy resources has helped diversify an agricultural economy. In 1951 an oil strike near Tioga, North Dakota, began a boom in the petroleum-rich Williston Basin. Extensive deposits of low-sulfur lignite, much of it near the surface, underlie the Northern Plains. Production by strip-mining, which arouses opposition from environmentalists, increased rapidly in the 1970s in North Dakota and southeastern Montana.

DERAILED BY ROADS - Rural roads and interstate highways have undercut traffic on feeder and some trunk railroads, whose passenger and freight traffic have been diminishing. Today south Dakota has no passenger railroads. The rise of long-distance truck transport has drained the vitality of many small railroad distribution centers. Auto and air travel have boosted tourism.

FEDERAL PROGRAMS - In 1934 work started on the U.S. Forest Service's controversial Shelterbelt Project, a 1,150-mile-long 100-mile-wide zone of windbreaks intended to reduce soil erosion and furnish jobs. It was abandoned, unfinished, in the early 1940s. But conservation techniques such as strip cropping and miles of local windbreaks attest to the lasting imprint of the government's Great Plains Conservation Program, initiated in 1956.