* Lesson plan idea - have your students update the information and latest statistics concerning the Northeastern Seaboard; discuss, contrast and compare the political, economic (employment), and environmental (climate change) situations of the area. • maps

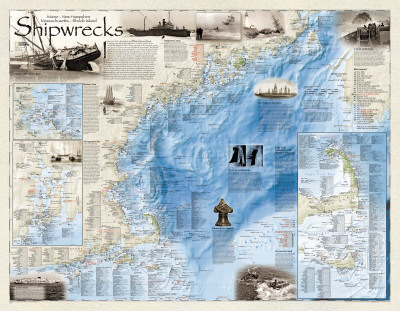

In the year 1634 a diminutive vessel named Sparrow Hawk, bringing critically needed supplies to Puritan settlers in the infant Massachusetts Bay Colony, wrecked on the perilous shore of Cape Cod. It was to become the first of more than 5,400 known shipwrecks on the untamed Atlantic coast of New England. From island rich Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island, to the scenic mouth of the St. Croix River, Maine, countless vessels, from five-masted schooners, frigates, and trawlers to elegantly appointed side-wheeled steamers, modern freighters and giant luxury liners, have defiantly sailed New England waters for nearly four centuries despite the dangers. Countless explorers, traders, whalers, watermen, warriors, and revolutionaries bravely ventured forth only to succumb to foul weather, combat, mutiny, unseen rocks, shoals, collisions, mechanical failure, human error, or myriad combination of all. Some shipwrecks played key roles in the very formulation of American history, folklore, and even literary traditions. A few actually carried pirate booty. Others, over time, would yield archaelogical treasures of even more value than gold, a better understanding of maritime America, who we were and how we became a seafaring nation.

Dangerous Coasts

The rugged, island studded coastline of New England is both splendid in its beauty and one of the most teacherous on the American coast. It has been the source of not only many tragic maritime disasters, but has also borne witness to countless heroic rescues. One such effort was successfully conducted by the U.S. Coast Guard on the wreck of the Oakey L. Alexander, lost on McKenney Point, Cape Elizabeth, Me., in March 1947 Another was by the U.S. Lighthouse Service on the wreck of the bark Annie C. Maguire, stranded on the rocks at Portland Head Light, Me., in 1996. Not so fortunate were the crewmwn of the square-rigger Jason, wrecked and broke up with all but one hand in a blinding snowstorm off Pamet River Life-Saving Station on December 5, 1895.

The Penobscot Expedition - In June 1779, with the War for Independence in danger of immitent collapse, British forces began construction of a base on the Penobscot River to secure timber for the Royal Navy shipyards at Halifax, and to block Americas potential advances toward Nova Scotia. The Massachusetts governance quickly launched a military expeditions to eliminate the threat to its borders. ...

Boston Area

As one of the great commercial entropots of North America, the Port of Boston, established in 1630 and first situated on a peninsula in Boston Harbor, has borne witness to numerous significant events of American maritime history. As a consequence of its role in national and international maritime affairs, it has also witnessed the loss of countless vessels with its harbor. Many more have been lost against its adjacent shores, islands, and on submarine ledges with colorful names such as Nantasket Beach, Lovell's Island, and Hardings Ledge. As the city expanded, a few historic shipwrecks, such as H.M.S. Diana, lost near Noodle Island on May 5, 1775, at the beginning of the American Revolution, during a fight between Patriot forces and the occupying British Army, no lay beneath land reclaimed from the harbor. Others, such as the great 74-gun man-of-war Le Magnifique, lost in September 1782, rests somewhere on the rocky, silt-covered bottom off the northwest point of Lovell's Island, patiently awaiting discovery.

Narragansett Bay

For the archaeologist, shipwrecks can put flesh on the bone of history, expecially where the written record is deficient. Rhode Island claims 2,000 such time capsules in its waters, more wrecks per square mile than any other state. One of the highest concentrations is in Narragansett Bay. The 29-mile-long embayment saw more than its share of historic events. The burning of the British schooner Gaspee on June 9, 1772, was a pivotal affair that helped set in motion the march towards independence. Another was the August 1778 destruction of ten Royal Navy warships and galleys, and at least four transports to prevent a French fleet from entering the harbor. Among the latter was Captain James Cook's famed ship of discovery Endeavor, which was employed as a trasport under the name Lord Sandwich. Many such vessels have become the subjects of significant archaeological investigation.

The Penobscot Expedition

In June 1779, with the War for Independence in danger of imminent collapse, British forces began construction of a base on the Penobscot River to secure timber for the Royal Navy shipyards at Halifax, and to block American potential advances toward Nova Scotia. The Massachsetts government quickly launched a military expedition to eliminate the threat to its borders. Under the command of Captain Dudley Saltonstall of the Continental Navy 3 navy ships, 3 brigantines, 13 privateers, and more than a score of armed transports from Massachusetts and New Hampshire carried 2,000 men to the front. Delayed by internal dissension among it leaders, however, the expedition faltered. On August 12, a relief force of 1,600 soldiers from Sandy Hook, NJ, carried by a Royal Navy squadron of 10 ships, arrived to reinforce the British garrison. Saltonstall's forces, bottled up in the Penobscot, were forced to flee up the river, and were soon grounded, abandoned, and destroyed in the worst American naval disaster of the American Revolution. Archaeological investigation of the river in the early-1970s by the Maine Maritime Academy led to the discovery of several of the wrecks and excavation of the 14-gun privateer brig Defence in Stockton Harbor.

The Great Portland Gale

One the evening of November 26, 1898, the elegant sidewheel passenger steamer Portland (built in Bath, ME.) set sail from Boston bound for her home port and namesake, Portland, Me., with 192 passengers and crewman aboard, As she departed for the often harsh “Downeaster” run, the weather began to rapdily degenerate into a ragin gale. For the next 36 hours the near-hurricane force winds raised havoc not only at Boston, but from Marraganset Bay to the Bay of Fundy. Finally, in the arly hours of Novemember 28, the storm subsided. Damage reports flowed in. When the final tally was made, it was discovered that one of the most deadly storms in New England history had claimed over 200 lives, and destroyed or sank more than 140 major vessels and untold number of less craft. No less than 30 ships had been wrecked or foundered in Provincetown Horbor, Mass., alone, and many more on both sides of Cape Cod. But the most dreadful loss of all was the noble steamer Portland, which disappeared with all aboard. Portland's final resting place would remain a mystery until discovered almost a century later in the heart of the Gerry E. Studds Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary.

U-Boats on the Coast ...

With the onset of America's entry into both World War I, and later, World War II, the shipping lanes of New England were severely accosted by German submarine offensives. More than 40 ships were lost to enemy attack during both conflicts. On August 10, 1918, as World War I was nearing a close, no less than seven vessels succumbed to enemy torpedoes and shellfire. The next conflict was no less deadly. Anti-submarine patrols by the U.S. Navy and U.S. Coast Guard, however, also inflicted losses upon the enemy, sinking several U-boats. On May 5, 1945, minutes before the formal end of the World War II in Europe, the U-853, having just torpedoed the American collier Black Point, was herself sunk by U.S. Navy depth charges seven miles northeast of Block Island, Rhode Island, becoming the last casualties of the Atlantic naval war.

The Great Oil Spill ...

On December 15, 1976, the Argo Merchant, a 644-foot-long, 18,743-ton Liberian flag oil tanker, was en route from Punta La Cruz, Venezuela, to Salem, Mass., laden with 7,700,000 gallons of oil. Owing to high winds, ten-foot seas, and major navigational equipment failure, the ship veered 27 miles off her intended course and stranded on Fishing Rip Shoal, 30 nautical miles southeast of Nantucket Island. Six days later the ship broke in half promulgating the worst marine oil spill disaster in American history to that date.

Pirates of New England ...

From the very beginning of English settlement along the New England coast piratical activities thrived. In 1632 Captain Dixie Bull became the first known pirate to operate in New England waters, primarily in and around Penobscot Bay. Over the next centruy many other notorious brigands, such as John Rhodes, Thomas Pound, Thomas Tew, John Quelch, and Ned Low would follow, becoming household names along the North Atlantic seaboard. Many, such as Captain William Kidd, who as arrested in Boston, would end their lives in a hangman's noose, others lost in battle or storms. Perhaps the most famous pirate of all was “Black Sam Bellamy” of the Whidah galley, which came to grief on Cape Cod on April 26, 1717, along with most aboard, and a fortune in gold. In October, six piratical survivors were executed in “the hanging port” of Boston, after which the Reverend Cotton Mather published a fire and brimstone sermon entitled “Warning to Then that Make Haste to be Rich.” On July 23, 1954, treasure salvor Barry Clifford announced to the world the discovery of th wreck, the first true pirate ship ever discovered, off Wellfleet, Mass. By October 1985, 268 years after the loss of Whidah, Clifford was reported having recovery $14 million in gold and silver, and myriad artifacts, including the ship's bell.

Wreck of the Albert L. Butler

A ship is one of the largest machines invented by man to perform a specific function, whether it is for transportation, trade, war, exploration, fishing, or numerous other services. Its very operation provides the basis for a unique human social order, maritime society, replete with its own laws, hierachy, customs, foodways and traditions. Thus, the loss of a vessel, such as the once picturesque merchant schooner Albert L. Butler, wrecked on Peaked Hill Bar, Cape Cod, Massachusetts, during the terrible Portland Gale of 1898, constituted not only and economic loss but oft times a human tragedy as well.

Andrea Doria ...

The night was dark and foggy at 11:10 p.m. July 25, 1956, when two great ships, the Italian luxury liner Andrea Doria and the M/V Stockholm of the Swedish American Line collided off Nantucket, Mass. When the 29,100-ton Doria, the largest and fastest Italian ship afloat, finally went down 11 hours later, 1,600 passengers an crew were rescued, but 46 more perished. It was to become the most infamous shipwreck in New England history.

Cape Cod, Nantucket, and Martha's Vineyard ...

Shaped like a man's arm, bent inward at both elbow and wrist, the 65-mile long peninsula of Cape Cod, Mass., and the adjacent islands of Nantucket, Tuckernuck, Muskeget, Cutthunk, and Martha's Vineyard, were discovered by Bartholomew Gosnold in 1602. Gosnold promptly named the great peninsula for the codfish that he found in incredible abundance in the surrounding waters. Soon after the arrival of the first settlers from Europe aboard the Mayflower in 1620, these same waters began to provide their bounty for the new colony of Massachusetts Bay, and eventually, over the coming centuries, a nation and world. From the busy harbors of Provincetown, Chatham, Nantucket, Edgartown and others, thousands of intrepid mariners woruld dare the innumerable hazardous shoals, submerged ridges, fickle winds, and countless “nor'easters” to harvest the finny resources of the Atlantic on the great Georges Bank and elsewhere. Many more would sail the world in search of whales, trade, and the treasures of the Orient. Such endeavors were not without cost as scores of vessels would be lost every year, usually in dirty weather, on such ship killers as the Peaked Hill Bar, Pollock Rip, Shovelful Shoal, and myriad others. Many sailing vessels would come to grief during great storms, some while riding them out in harbors of refuge, or driven onto the backside of Cape Cod. Others would be lost upon small islets, in passage through narrow, or while rounding points of land. In all nearly 1,500 vessels would meet their doom here, nearly 900 of them on Cape Cod alone.