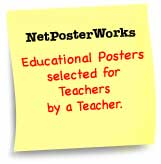

The 1991 Native American Heritage map features:

• Four regions and how they greatly defined the lives of the nations first inhabitants

• Native American sites including tribal centers or museums, archaeological or historical sites, and museums with Native American exhibits

• Federal Indian reservations

• Selected national parks, recreation areas, and monuments

• Interstate highways and other roads

• Illustrations of Native American artifacts

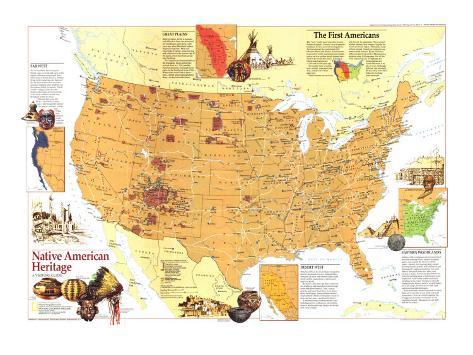

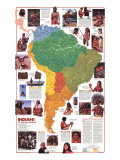

* Lesson plan idea - have your students update the information and latest statistics concerning the indigineous populations in the Americas; discuss the political, economic, and environmental situations that are current for the region. • maps

The “new” world wasn't novel to its early human occupants. It wasn't even a separate landmass, for low sea levels during the Ice Age had exposed the continental shelf between Siberia and Alaska. Asian hunters in pursuit of woolly mammoths and smaller quarry such as caribou simply pressed eastward n the world they knew, arriving in North America between 12,000 and 40,000 years ago.

Eventually their world was new: warmer, separated from Asia, and devoid of their giant prey.

Native Americans survived, and thrived, by adaptation. They hunted smaller animals; they foraged, tapping the resources of each region. Ultimately, many of them farmed. Varied environments sustained varied cultures: By the 1500s two million people lived north of Mesoamerica, speaking some 300 languages. Out of this vivid cultural mosiac five broad regions are highlighed. Strikingly different and internally diverse, they were often linked by far-flung trade networks.

EASTERN WOODLANDS – Indians of the woodlands speared and netted fish from teeming rivers, hunted abundant game, and scoured the forest for edible plants. About 3,000 years ago they started growing squash, gourds, and sunflowers, yet farming only supplemented their diet until about a thousand years ago, when corn became a staple. Eastern peoples felled trees from the plentifual stock to build homes: bark longhouses in the north, wattle-and-daub dwellings in the south. Farming eventually brought a new form of society, as settlements grew into large, fortified towns with rigid castes and specialized artisans.

Early easterners erected long tombs for their dead, who were laid to rest amid treasured possessions. Over each burial chamber the living poured countless basketfuls of soil, creating a mound. Thousands of such hills still dot the region.

GREAT PLAINS – Bitter in winter, torrid in summer and difficult to farm, the plains had few inhabitants until about 2,000 years ago, when Woodland Indians began moving west. They took knowledge of pottery, stone carving, and cultivation to the eastern edge of the plains, where thy built permanent dwelling.

Two imports revolutionized life on the grasslands. Bow and arrows arrived about A. D. 500, possibly from the subarctic; European horses came via the Southwest in the 1700s. Whole tribes soon lived on horseback – folded tepees trailing behind them – as they hunted for bison.

DESERT WEST – Patterns of life in the Great Basin changed little over thousands of years. Isolated tribes subsisted on seeds and whatever they could catch; rabbits on good days, rodents and insects to get by.

By about 2,000 years ago their sourthwestern neighbors had learned farming through trade with Mesoamerica. Corn, squash, gourds, and beans freed them from dependence on foraging. Some sourthwesterners dug hundreds of miles of irrigation canals to coax two harvests a year from the desert.

A millennium ago southwesterners were building pueblos, settlements whose thick stone or adobe walls kept rooms cool by day and warm at night.

FAR WEST – No one needed to farm along the Pacific coast, even though parts of this region had many more people than other areas of North America. Indians living in the temperate rain forests of the Northwest feasted on sea mammals and shellfish; their neighbors on the plateau fished for salmon. Northwestern villages, built of cedar planks, often sprawled over several acres; their residents ranged from hereditary nobles to slaves.

California had some 500 tribes – most lead by a headman – who foraged for specialites: acorns, perhaps, or pinenuts. Tribes used shells in trade with one another.

ARCTIC & SUBARCTIC – Sheltering themselves on bleak terrain, Arctic peoples used anything at hand. They built winter dwellings of stone and driftwood overlaid with sod. In summer they occupied anima-skin tents, supported by wood or whale ribs. They hunted walruses, seals, and other plentiful sea mammals.

Subarctic peoples, like their northern counterparts, hunted with bows and arrows. They used birch bark to cover the frames of their canoes, and they trimmed their clothes with porcupine quills colored by dyes from berries and fungi.

..........

America's first known occupants, Paleo-Indians, left stone weapon tips through much of North America - Clovis points. Hundreds of tons of chert for points, knives, and scrapers were mined at Alibates Flint Quarries National Monument in Texas. Experimenting with replicas, scientists have confirmed that Paleo-Indian tools worked well for butchering mammoths.

Three thousand or so people once occupied what is now Alabama's Mound State Monument, known as Moundville. Visitors can see a reconstructed temple on a platform mound built by Indians lugging basket upon basket of dirt. Workshops here and at other mound sites turned out shell carvings and pottery in distinctive styles. Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site in Illinois boasted a greater population – more than 10,000 – between A. D. 1000 and 1200. Monks Mound at Cahokia covers 14 acres.

Moundville and Cahokia represent a high point of eastern culture. An earlier blossoming took place in the Ohio Valley around 500 B.C. Carvers there fashioned stone pipes to smoke a variety of plants, possibly including tobacco mixed with sumac. A pipe that seems to portray a dwarf, found in 1901 during one of the area's first excavations, can be seen at the Ohio Historical Center, whose exhibits range from Paleo-Indian to recent times.

Four sites provide examples of the diversity of structures - Louisiana's Poverty Point has concentric ridges that may have supported thatched houses. A circle and an octgon are but part of what were wast ceremonial earthworks built later at Newark, Ohio. With wings spanning 150 feet, a 1,500-year-old bird mound is one of 29 giant animals at Iowa's Effigy Mounds. At Georgia's Etowah site has platform mounds once topped with temples whos ornate trappings typified southeastern rituals from about 1000 to the 1500s.

White and purple shells, or wampum, were woven into belts used in rituals and trade in the Northeast. One such belt was passed down by leaders of the Seneca, who sent it to other Iroquois nations to notify them that the Seneca had undertaken a war on behalf of the Iroquois Confederacy. Today it also symbolies the thorny questions of artifact ownership. The Seneca consider the belt – owned by New York State but lent to the Seneca-Iroquois museum – part of their heritage. Some institutions, including the Smithsonian, have begun returning artifacts to Indian groups.

For all his hold on the imagination, the mounted Plains warrior was a latecomer in Indian history; inhabitants of the plains lived much like their eastern neighbors until the arrival of the horse. They even built mound – which can be seen near Spiro, Oklahoma. Spiro's modern history began in 1933, when treasure hunters dynamited the site and carted off its artifacts in wheelbarrows. (Spiro Mounds Archaeological Center) Looting remains a threat to Indian sites, robbing Indians of their heritage and everyone of knowledge that archaeologists might have gained from analysis of objects in their precise locations.

Parts of the Great Plains had more people in Indian times than they do now. More than 20 villages, some with nearly 4,000 people, lined the Missouri River near the Knife River in North Dakota. Their inhabitants acquired horses in the 1700s but remained agricultural. Elsewhere, most Plains tribes abandoned their crops for a new nomadic life on horseback. Elaborate horse masks of porpupine quills testify to the Indians' reverence for the creature that remade their lifeways.

Carved about a thousand years ago, a petroglyph is southeastern Utah dipicts a hunt for bighorn sheep. Petroglyphs can be seen throughout the continent, notably in Nevada's spectacular Valley of Fire. Arid caves in Oregon preserved sandals, woven as early as 8000 B.C., that are among the hemisphere's oldest surviving textiles. They are displayed at the University of Oregon's Museum of Natural History in Eugene.

Not until the 19th century did immigrant Americans build multifamily dwellings large enough to rival those of the Southwest Indians. Colorado's magnificent Cliff Palace had some 220 rooms, not counting the 23 kivas, or round ceremonial chambers. The rooms may have been arranged into suites to shelter extended families. Cliff Palace is the centerpiece of Mesa Verde National Park, whose attraction include numerous smaller pueblos and a museum.

A rabbit motif decorates a southwestern bowl made between A.D. 750 and 1150. Potters also favored peometric designs, frequently black on white. Vessels found at some southwestern burial sites have small holes in the bottom – perhaps resulting from the ritual “killing” of the bowl, to release its spirit along with that of the deceased.

The Anasazi, most celebrated of southwestern cultures, flourished at Chaco Canyon in New Mexico. Pueblo Bonito was the largest of the canyon's many “great house” complexes. Sandstone walls, painstakingly constructed, enclosed 650 rooms, piled five stories high. To connect their pueblos, these Anasazi laid out 400 miles of amazingly straight roads, some of them 30 feet wide.

Mud slides five centuries ago buried part of Ozette, a whaling village in Washington more than 2,000 years old, creating what has been called the American Pompeii. So well was the village preserved that researchers found sleeping mats still on benches and wood chips littering an artisan's work area. Exposed by a storm in 1970, the site has yielded 95,000 objects, some on display at the nearby Makah Cultural and Research Center.

Travelers in Canada can find not only an array of artifacts from the Northwest but also reconstructed Haida houses at the University of British Columbia. The large clan dwelling is fronted by the family totem pole. Next door is a mortuary house whose pole commemorates the clan's ancestors.

A killer whale decorates a blanket braided of cedar fibers and mountain goat hair. Whaling was orchestrated by the elite of the Northwest's status-conscious villages. On land, families polished their reputations through gift-giving parties called potlatches, where they would lavish blankets, carvings, canoes, and even slaves on their guests–who were honor bound to reciprocate eventually. Potlatches continue to this day.

And so do spirit dances and stickball matches and serpent rituals and Green Corn Ceremonies. So, too, the centuries-old labor of potters, weavers, mask makers, and pipe carvers–all of them producing not mementos of lost cultures but the crafts of the peoples who still adapt and endure.