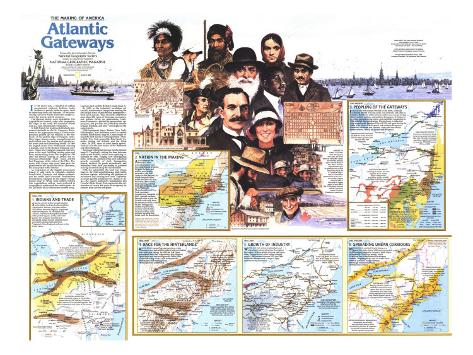

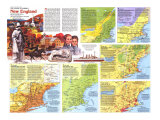

* Lesson plan idea - have your students update the information and latest statistics concerning the Atlantic coast of North American - states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island in the United States and the Canadian Maritime Provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland, and southern Ontario; discuss, contrast and compare the political, economic (employment), and environmental (climate change) situations of the area. • maps

IN THE EARLY 1600s, a handful of settlers encountered scattered Indians; today millions of people jostle for space, most in sprawling cities and suburbs. In the intervening years new North Americans sought access to the interior and its resources.

The physical barriers were formidable. The Appalachians loomed, ridge after impenetrable ridge; in the north the Canadian Shield rose as a vast, inhospitable wilderness.

In 1608 French fur traders established a permanent foothold on the St. Lawrence River, home of the Algonquins. Dutch entrepreneurs pushed up the Hudson to the Mohawk, at the eastern edge of Iroquois lands. Here began intense rivalry among Europeans and Indians over fur sources and gateways–the rivers and trails threading inland. In 1664 the English seized New Netherland, winning a strategic prize in the Hudson-Mohawk corridors. France and England expanded their empires to the west, building trading posts and forts, mortly along rivers. War erupted in 1754 after the French–aiming to protect the St. Lawrence-Mississippi trade route–erected Fort Duquesne at the forks of the Ohio. The treaty with France nine years later gave England control of Canada and the St. Lawrence, the main portal to the interior.

As proprietors of the English possessions leased or sold tracts to colonists–English, Scotch-Irish, Germans, and others–competitons for arable alnd increased. Southeastern Pennsylvania emerged as the region's breadbasket. While some settlers filtered in Appalachian valleys, most preferred to congregate in and around the eastern ports. As the last shots of the Revolution echoed away, Loyalists fled north to British Canada.

By 1830, as the industrial revolution advanced, northwestern Europe was sending the first major wave of non-British immigrants–Irish and Germans. They found the imprint of more than 200 years of European occupancy, and Indians living on reservations. Later, more Europeans–pushed by persecution, oppression, and poverty and pulled by dreams of land, freedom, and jobs–converged on the eastern ports.

With immigrant labor, Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore raced to exploit western hinterlands. Crude roads offered the first means of defying terrain. Then, in 1825, New York opened the Erie Canal, in a stroke joining the Atlantic and the Great Lakes. In 1829, even as canal mania spread, workers laid the first tracks of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

Railroads redoubled the race for the interior. Drastically cutting the time between Albany and Buffalo, trains were replacing canalboats by 1860. Forging new interregional links, railroads sparked urban and industrial growth, especially of steel. Immigration soared, demand for goods skyrocketed, and industries from food processing to garment making clustered along the rail corridors.

With the automobile the road was reborn. By 1960 superhighways sped traffic between regions, reinforcing old patterns of movement and creating new ones. Explosion in urban growth produced two chains of cities–the eastern seaboard's megalopolis and Canada's Main Street. Each represents the culmination of nearly 400 years of occupancy by peoples from around the globe.

1. 1600-1760 - INDIANS AND TRADE - SEEKING ACCESS to the fur-rich interior in 1600s, the French allied with the Algonquins, Hurons, and other tribes. The Dutch, then the English, negotiated with the Iroquois. At Montreal and Albany, Indians exchanged beaver and other pelts for guns, cloth, and metal goods. The Iroquois Confederacy disrupted Indian-French commerce and eventually dominated trade from Virginia to New England and west to the Great Lakes.

HURON DISPERSAL - To strengthen its position in the fur trade, the Iroquois Confederacy waged a continuing war on the Hurons. In 1649 surviving Hurons abandoned their villages and dispersed. The Iroquois also defeated other tribes such as the Erie and the Susquehannock.

TUSCARORA MIGRATION - Driven from North Carolina in 1713 by land hungry colonists, 500 families of Tuscarora Indians, vanguard of an extended migration, fled north to become the sixth nation of the Iroquois.

2. 1770 - NATION IN THE MAKING - AFTER defeat of the French in 1763, colonists pushed west. Growing frontier tensions between Indians and settlers were briefly defused by the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix, in which Iroquois tribes ceded land east of a new boundary. Meanwhile, long-standing colonial boundary disputes, such as that between Massachusetts and New York, persisted. Connecticut, chartered in 1662, claimed northern Pennsylvania as part of a 70-mile-wide strip from the Delaware River to the Pacific. Struggle for control of part of this territory led to battles between settlers with contrary loyalties that lasted until the Revolution.

3. 1790 - PRESENT - PEOPLING OF THE GATEWAYS - EMIGRATION from Europe swelled by the 1850s. Irish and Germans poured in to dig canals, lay railroads, and labor in factories. By the turn of the century another wave swept in, the time of central, eastern and southern Europeans. It broke over the cities, manufacturing towns, and coal fields. Legislation in 1924 curtailed this immigration. Blacks drawn to industrial cities surged north between 1916 and 1918 and again during the 1940s. After World War II central and southern Europeans diversified Montreal and Toronto. Today the New World dream endures, mostly for Asians and Hispanics.

IMMIGRANT DESTINATIONS - By 1830 the richest farmlands had been taken; growing cities attracted most later immigrants.

NEW ENGLAND EXODUS - The lure of rich land sent Yankee farmers into central and western New York. The state's hinterland population jumped from 9,000 to more than 700,000 between 1790 and 1820.

PUERTO RICAN INFLUX - Following the world's first mass migration by air, Puerto Ricans –exempt from immigation quota – by 1980 swelled New York State's population by nearly a million.

SOUTHERN BLACKS MOVE NORTH - Although widely dispersed in the gateways region, many gravitated to New York City, where blacks and lived since colonial times. Harlem became their cultural hub by 1920.

4. 1800 - 1840 - RACE FOR THE HINTERLANDS - ROUGH ROADS opened up regions where water transport was unavailable; others followed Indian trails and river valleys. By 1825 the Erie Canal guaranteed New York's supremacy and triggered agricultural and industrial growth. Other ports scrambled to dig canals, such as those from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh and Washington to Cumberland.

CANALS AND COMMERCE - Wheat and lumber from the interior reached New York City via the Oswego Canal; such feeder canals on the Erie furthered New York's dominance.

NEW YORK CITY - Despite competition from Boston, globe-girdling clipper ships and eventually transatlantic steamboats consolidated New York's position as North America's premier port.

PENNSYLVAINA MAIN LINE - Canal system linking Philadelphia and Pittsburgh included a portage over the Alleghey crest; canalboats were loaded atop flatcars and wrenched over the summit.

5. 1840-1910 - GROWTH OF INDUSTRY - WATER AND RAIL access to abundant coal stimulated industrialization throughout the region. With available iron ore and cheap labor, Pennsylvania's steel output jumped nearly 1,000 percent between 1874 and 1884. Railroads also attracted a range of light manufacturing industries.

RUTLAND RAILROAD - Built in the 1840s, the railroad from Boston to the St. Lawrence failed to capture a major share of interior trade.

COAL FOR IRON AND STEEL - In the 1840s anthracite fired iron furnaces in northeastern Pennsylvania. By 1880 the high-quality bituminous coal in the Pittsburgh area was being used for steel.

IRON-ORE SUPPLIES - Steelmakers in the western region relied on ore from the upper Great Lakes; later those in the East turned to imports.

6. 1945 - PRESENT - SPREADING URBAN CORRIDORS - MEGALOPOLIS,, anciet Greek vision of a grand city-state, found different expression in 20th-century America. Canada's Main Street is lined with 12 million people, while 50 million live in the Boston-Washington corridor. Superhighways and air routes form intercity lifelines, while beltways encourage expansion around metropolitan centers.

HINTERLAND CITIES - Merging industrial centers and residential communities across central New York and western Pennsylvania form urban strips linking megalopolis and the Great Lakes. Nearby forested uplands lure city-weary millions every year.

REVOLVING DOOR OF MEGALOPOLIS - Immigration has not offset local population losses as heavy manufacturing declines. As computers cut ties that concentrate industry, Sunbelt migration may quicken.

URBAN EXPANSION - Suburbia and exurbia with malls, industrial parks, and commuter countryside link expanding cities and signify the legacy of the automobile.