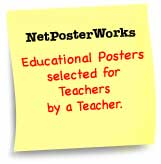

The 1974 Discoverers of the Pacific map features:

• A map showing the travels of Pacific Islanders and how various islands were discovered

• Information on Pacific Islanders, their history, and their extraordinary sea-faring abilities

• Illustrations and information on the canoe-building practices of Pacific Islanders

• Illustrations and information about many types of canoes

• “Steering by Stars and Sea” article with illustrations to show how islanders navigated

• Illustrations of various peoples who inhabited the Pacific

• Illustrations of native shipbuilding tools

* Lesson plan idea - have your students update the information, discuss the political, economic, and environmental situations at time of publication and at date of their research. • maps

THE SEA PEOPLE

Nightfall in the Marshall Islands. Miles from land, a solitary outrigger canoe tosses in the roiling swells. In the bilge of the canoe, a man lies on his back, silent, his every sense attuned to the slap of wave upon hull, to the rhythm of the dance between his vessel and the sea. Incredibly enough, he is fixing his position–at night, in the open ocean. From years of training and experience, he knows that ocean swells, rebounding from islands in his archipelago, form patterns that vary from place to place. By interpreting his canoe's response to the swells, he knows his location.

He is a navigator. A navigator without compass, chart, or sextant, but a navigator nonetheless, and one of the last remnants of a determined breed of voyagers–the Polynesians, the Micronesians, and to some extent, the Melanesians–who discovered every habitable island of the vast mid-Pacific from New Guinea to lonely Easter. They accomplished all this before Columbus set sail, before Viking ventured westward.

They voyaged in canoes hand-hewn from trees, lashed with coconut fiber, and rigged with sails of plaited leaves. Rugged, seaworthy, their vessels excited the admiration of European sailors. “They sail the best of my Boats in the World,” noted the English buccaneer William Dampier of canoes he saw at Guam in 1686. Of the Hawaiian outrigger, the missionary William Ellis observed, “One man will somtimes paddle a single canoe faster than a good boat's crew could row a whale-boat.” One of Captain Cook's crewmen paid this tribute to the Tongan seamen: “These Canoes rund us nearly out of sight ... they sail about 3 Miles to our two ...”

Where did they come from–these dauntless explorers of the Pacific? The Polynesian languages, plants, and domestic animals –pig, dog, and jungle fowl–suggest an origin in the islands of southeast Asia. Their immediate ancestors were the Lapita people, ancient voyagers known mainly by the pottery they scattered from new Britain to the cradle of Polynesia, the islands of Tonga and Samoa. here, from perhaps only a few families, the people we know as Plynesians evolved.

Around the beginning of the Christian Era, they pointed their canoes into the blue infinity eastward, into an area of ocean more than four times as large as the United States, to discover a galaxy of islands whose total land area, excluding New Zealand, is not quite that of New Hampshire.

Were their discoveries planned? Or were they accidental–canoes driven by wind or storm on one-way trips to new landfalls? Scholars fitting together the pieces of the past still debate the question, but the majority theorize that many were voyages of exploration, deliberately planned and skillfully executed.

When the Europeans arrived, the heyday of Polynesian exploration had long since passed; Western accounts of the naivgational techniques of the Pacific peoples are fragmentary and inconclusive. Captain Cook observed that they sailed with “the Sun serving them for a compass by day and the Moon and Stars by night.”

In 1965 Dr. David Lewis, an accomplished navigator who had made three solo crossings of the Atlantic, put theory to the test of sail. Disdaining conventional instruments, using only the signs of the sky and the sea, he sailed from Tahiti to New Zealand, and made his landfall with only 26 miles of error. Later he voyaged with navigators of he western Pacific, absorbing the seagoing lore of men who still roam the open ocean as did their forebears.

For the Pacific Islanders of old, the canoe was the lodestone of life. Some voyages were forced–by lost battles, famine, even outraged husbands. Others were for gift-exhange, to be tattooed (tatau is a Polynesian word), to gain the status of explorer, or just to relieve boredom. Only in a few remote islands does the ancient urge to go a-voyaging persist, where trips of several hundred miles are made to reaffirm manhood, or, if anyone should ask, to buy cigarettes.

STEERING BY STARS AND SEA

Unlike the early European navigators, who feared sailing off the edge of the world, Pacific Islanders faced the ocean with confidence. For the Polynesian, god-ancestors ruled an orderly universe. When the sun, moon, and planets kept to their appointed paths, when stars predictably rose and set, when the sea itself was the bosom of the ancestor Tangaroa–what was he to fear?

But there was much for him to respect: the dangers of voyaging, of ships and men wrecked upon a reef or foundering amid storm-tossed waves. Nevertheless, the Polynesians saw such misfortunes as arising from faults of their own, such as a helmsman who erred in navigation, or one who failed to observe an obligatory ritual.

The Pacific mavigator trusted hsi gods, but at the same time he trained hispowers of observation. His compass was the position on the horizon of some 150 rising and setting stars, his chart a mental record of current and swell patterns. For him the flight of a bird, the shape of a cloud, a bit of flotsam were significant signals pointing the way to this goal–land beyond the horizon.

Embarking at sun set, a Tahitian navigator sets his course to a known destination by aligning his pahi with two mountain peaks astern. Drift of the canoe away from the peaks will tell him the direction and strength of the current. As dusk falls and landmarks fade from sight, he will pick up his next bearing from a familiar star.

STAR PATHS: Navigators steered toward stars known to rise over their destination island, a process usually complicated by wind and current. Buffeted by wave and wind for port, a helmsman (illustration) chooses a star well to the left of his desired course. He allows for the wind, which he can gauge by his leeway, or angle his boat makes with its wake, and for current, an angle he must estimate from experienc. Such corrections allow him to sali true to his landfall. “I cannot miss my island,” says a Tikopian navigator. “It is where I follow the stars.”

OCEAN SWELLS: Generated by distant winds, great undulating seas pulse the open ocean for thousands of miles, providing the navigator with yet another signal. He can maintain a heading by regulating his degree of roll, pitch, or combination of thetwo motions.

ZENITH STARS: Stars known to pass directly above an island gave voyagers it latitude. By approaching upwind of an island until its zenith star was overhead, the navigator could then turn due west and run with the wind to his destination.

FLIGHT PATHS: Heading for their fishing grounds at dawn, returning to their roosts at dusk, such seabirds as frigates, terns, and boobies point the direction to their island homes. Fed by warm updrafts from its parent island, cumulus billows thousand of feet skyward and remains stationary, while smaller clouds drift away to sea.

SIGNPOSTS OF THE SEA: Deepwater blue changing to green betrays a familiar reef, enabling the navigator to check his position. Driftwood hints that land lies to windward, while seaweed indicates an up-current reef. Light green underside of a cloud heralds the presence of the distant lagoon.

SWELL PATTERNS: Main swell bounces back from an island, and bends around it, creating swell patterns that reveal the island's bearing. “I feel the sea hit the canoe, shake him, like move him go back,” says a Polynesian. Meeting the reflected swell at an angle, the navigator turns into it and proceeds toward his unseen landfall.

ISLAND BLOCKS: Birds, cloud formations and other signs of an unseen island expand a pinpoint land fall by a radius of 25 to 30 miles. In island groups the circles overlap, forming a screen hundreds of miles wide. Sailing from Mitiaro to Tahiti, a voyager could aim for the center of the Society Islands, then change course after spotting familiar land.

SHIPS WITH SOULS -

The building of a conoe was a religious event, marked by prayers, ceremonies, and feasts. On the last night of the moon before construction began, Tahitian craftsmen “put their adzes to sleep” in a sacred place, and implored Tane, god of the land, to charge them with his power. Next morning, the men “awakened” their adzes by dipping them in the sea, and work proceeded.

Since trees were the children of Tane, the workers invoked the god's permission before felling them. Wielding a stone adz, prime tool of a people without metals, a woodsman made concave cuts around a tree trunk, then chopped away the wood between the cuts.

With songs and chants, the entire community turned out to haul the great logs to the canoe yard. There the adz fairly flew, as an artisan hewed a keel or carved a dugout. When blades grew brittle with heat, craftsmen cooled their adzes by plunging them into the moist trunks of banana trees, then sharpened them on blocks of sandstone.

Green logs were heated on a fire until they split. With weges and maul, a workman chiseled off planks for a sailing canoe's full and deck, then adzed them to shape.

Children brought strips of pandanus leaves to the women, who plaited them into sails with a texture almost as fine as cotton. Gossiping old men rolled coconut-husk fibers into string on their thighs, then braided it into a cord called sennit.

The builders lashed hull planks together with the sennit, again involving the assistance of Tane: “This sennit of thine, O Tane, make it hold, make it hold.”

To join a gunwale plank to a dugout hull, Hawaiian craftsmen chiseled cavities along the plank' botton, then drilled holes from side and bottom to meet the cavities. They also drilled holes into the hull. After laying a smear of breadfruit sap for caulking, they lashed hull and plank together with sennit.

Tuamotuans carved planks to a precise fit edge to edge, battened the seams with coconut-frond midribs, then bound them with sennit tightened with a forked stick. A caulking spike plugged holes with wads of coconut fiber.

In Samoa, planks were carved with flanges along the interior edges then lashed together through holes in the flanges.

The all-purpose sennit bound a Marshall Islands outrigger float to its booms and lashed the outrigger boom to the hull of a Hawaiian wa's kaukahi. Hull planks of the Fijian ndrua were adzed to exact curvature, then lashed with sennit. Vertical ribs added strength.

Hawaiians snaked loops of sennit along the mast to secure the sail. Samoans pegged outrigger float to boom, then secured the assembly with lashings.

Amid feasting and fine dress, the community witnessed the launching of the canoe. Built under the tutelage of the gods, the vessel was regarded as possessing spiritual power, and was welcomed by the people as a living member of the community. When a tree in Hawaii was about to fall, the priest shouted: “Now you are a tree, soon you will become a man.”

Construction of a large canoe could take years– the mighty ndrua as many as seven. Since Fijian chiefs paid their craftsmen with feasts, the faster the work, the more frequent the feasts. “A tata tu i kete– The chopping is in the belly,” ran a proverb.

CAPTIONS FOR ILLUSTRATIONS -

Helmet and cape of a Hawaiian noble required the feathers of thousands of bird.

Pigeon feathers of iridescent green emblazon the helmet of a Tahitian ruling chief

Sennit helmet crowns a Cook Islands warrior.

Marquesan chief wear wooden ear ornaments and wields a rosewood club.

Samoan taupou–a highborn maiden of sacred status–wears a headdress of feathers, shells, and an ancestor's bleached hair.

Blowfish helmet and sennit armor shield a Gilbert Islands warrior. Shark's teeth edge his sword.

Boar's-tusk pendant and a comb of coconut-frond ribs lashed with human hair adorn a Tongan warrior. He carries a ironwood club.

White tapa turban and a breastplate of pearl shell and ivory array a Fijian chief.

Face scrolled with tattos, a Maori chief of New Zealand clutches a jade war club.

Tevake of the Santa Cruz Islands–one of the last of the Polynesian navigators and tutor to Dr. David Lewis. In 1970 this aging and proud man, sensing he would soon become a burden to his family, bade farewell to them and paddled out to sea in a frail canoe, never to return.

Bow becomes stern, stern becomes bow. All Micronesian and some Polynesian voyaging canoes had double-duty bows and sterns, and could sail either end forward. Thus tacking was accomplished by shifting the sail from one end to the other, while keeping the outrigger to windward. A Nukuoro crew demonstrates (illustration) 1) Helmsman turns into the wind, luffing the sail, 2) His mate carries the sail rig aft. 3) Sail secured, positions swapped, the helmsman steers the canoe on its new tack–all in a matter of seconds.

Amatasi, Cowrishells decorate this graceful Samoan fishing canoe.

Kaep. For swift sailing, the crews of this slim-hulled racing canoe of Palau moves aft, lifting its bow and part of its knife-edged keel out of the water.

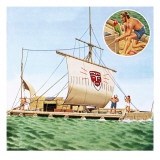

Ndrua. Dreadnought of the Pacific, this 80-foot Fijian craft carried more than 200 warriors at speeds of up to 15 knots. Samoans and Tongans built similar vessels, known as ‘alia or kalia. An English missionary tells of a voyage on a kalia in 1846: “Up went the huge sail ... and away we shot like a racehorse ... Every timber ... creaked ... while the mast bent like a reed, and cracked in its socket as if it would split the deck in two ... the sea was like a hissing cauldron ... and the kalia, instead of having time to mountover the smaller waves, cut its way right through them.”

Pahl. Carved tikis crown the upswept bow and stern of this deepwater voyager of the Society Islands.

Pahi. Master shipwrights, the Taumotuans fashioned a crazy-quilt of planks into a superb vessels that roamed their 1,000-mile-long archipelago–and sailed west to Tahiti.

Popo. Little changed since 1579, when Sir FancisDrake's crew observed them as “cut with great arte, and cunning,” these outriggers of the central Carolines still embark on voyages of hundreds of miles.

Te Puke. Voyaging canoe used by the navigator Tevake.

Tongiaki. Fair-weather voyager, this Tongan canoe became a maverick in storms, requiring several men on the huge steering paddles.

Va'a Hou'ua. Graceful as seabirds, curved sternpieces adorn this double-hulled Marquesan canoe, helping to blunt waves of a following sea.

Vaka. Dolphinlike bow distinguishes this trading canoe of Pukapuka. It could carry several tons of copra.

Wa'a Kaulua. “Well calculated for speed,” wrote a 19th-century observer of this sleek hawaiian canoe. “We have seen the natives ... fairly run them under water.”

Waka. In quest of tuna and bonitl, this craft ventured far from its atoll home, Kapingamarangi.

Waka Taua. Powered by sail and paddles, a Maori war canoe heads for battle (illustration). Craftsmen adzed the hull from a giant log, designing the vessel for beauty as well as war with an intricate carving gracing the stern.

Waka Taurua. Canoe craftsmen of Manihiki in the Cook Islands adorned their vessels with rich inlays of mother-of-pearl.

Wa Lap. Frigate-bird feathers adorn masthead and sail of this voyaging canoe. Fanlike ornaments on prows indentify it as the vessels of a Marshall Islans chief.

War Canoe. With identifying battle streamers flying, rival Tahitian chiefs and their cohorts jousted from the raised platforms of such craft. In 1774 Captain Cook witnessed a fleet of 160 of these vessels, “very well equip'd, Man'd and Arm'd.” One canoe measured 108 feet, almost as long as Cook's ship Resolution.