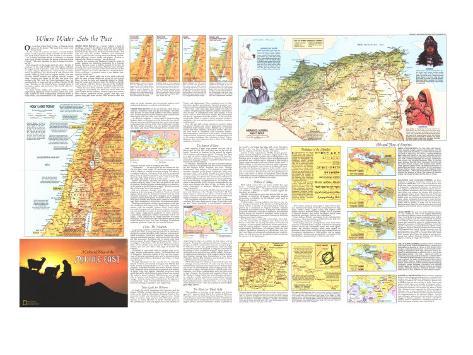

Where Water Sets the Pace

On a parched wheat field in Iraq, a Moslem farmer muses on the Koran: “We made from water every living thing.”

At the wheel of a tractor in Israel, a Jewish farmer-soldier recalls a promise made to Isaiah: “In the wilderness shall waters break out, and streams in the desert.”

On a thirsty mountain terrace in Lebanon, a Christian Arab apple grower murmurs the words of the poet Kahlil Gibran: “The Earth breathes, we live; it pauses in breath, we die.”

Each depends on the magic touch of water–the key to existence in the arid Middle East. The region embraces the largest swath of desert of Earth, from Atlantic beaches to Asian steppes. Blast-furnace winds sweep its heart, where temperatures rise above 130ºF. Salt poisons soils already suffering from lack of organic matter. Yet man surivives. Buried streams and springs nourish verdant oases. Crossing the desert to the sea, two great river systems–the Nile and the Tigris-Euphrates–have bequeathed gifts of water and silt to valleys tilled for 10,000 years. Wreaths on the desert's brow, gnarled bands of mountains gather rain and snow that enrich other fortunate valleys.

In these varied niches, man extends water's sway, engineering ingenious works: terraces, dams, and pipelines; tunnels to draw underground mountain water to valley fields; and waterwheels to fill irrigation channels.

THOSE WHO PLANT: In a Syrian village, a score of dwellings, awash in the khaki of sun-dried mud, huddle along dusty lanes. Their blank faces veil the complex home life of the farmer. In the main room the family–the man and wife, his mother, children, and unmarried sisters–gather for the evening meal of steaming cracked-wheat porridge, onions, bread, and yogurt. “If there is nothing else, bread is enough,” says a proverb.

During the evening the husband's relatives come to confer, sipping tea, warming themselves by a charcoal brazier. Because a man is held to account by his kin, he consults them on major decisions: Shall we buy a donkey? Is daughter's suitor a proper match? Since the beau is her father's nephew, he is most desirable as a husband. First-cousin marriage, a preferred union in the Middle East, cements family ties.

At dawn the farmer walks out to the small scattered plots he owns or rents. Behind an ox and an iron-tipped plow, he stirs the light soil repeatedly before he broadcasts the barley and wheat. In time, his children will help with reaping. Half the harvest may go to the landlord, another share to taxes, the rest to the family and to market.

While the man deals with the outside world, the wife manages the household: she bakes the bread, milks the goats tended by her children, cultures yogurt and cheese, sews clothes, preserves sauces, grapes, and figs, and gathers dung and straw for fuel. With no doctor near, she relies on herbs, amulets, and invocations against such widespread diseases as malaria and trachoma.

THOSE WHO ROAM: On the far horizon, black tents of nomadic tribesmen come and go like mirages. Nomads, who account for only about a tenth of the area's population, pursue pasture sired by fleeting rains to feed heards that supply milk and yield wool for cash.

As shadows lengthen, a weary band of camel-hearding Bedouin halts on the plains at a site chosen by their sheik. Women unfurl and pitch long goat-hair tents, spread rugs, and prepare the evening meal. After hobbling the camels, the men gather around to dip into platters of seasoned rice, dates, and bread. When strangers visit, women eat in seclusion behind walls of hanging tent cloth.

“Remember ...” an uncle starts the talk around the fire. Oft-told tales scorn settled life and honor ancestors who raided villages or exacted protection money. Tell again, a youngster implores, of the poor sheik and the unexpected guest. True to Moslem hospitatlity, the desert chief slaughtered his best riding camel for a feast–only to learn that the visitor had come to buy it at any price.

Before day breaks, the men are milkng camels, the women breaking camp. Then they are gone on the quest for pasture, clinging to their independence as to treasure. In the words of an old Pashtun nomand, “Would you trade the whole world for a little garden?”

But now dynamic changes come like desert winds, plucking at the tent pegs of tradition. Trucks and buses replace camel caravans. National borders break up trade networks of artisans, and make smugglers of far-ranging nomads carrying trade goods. Transistor radios, swinging from plow handles and saddle horns, speak of moon landings, heart transplants, and politics in the neighboring lands.

Battling rural poverty, national governments reach into the hinterland with many tools. Modern law, backed by armies, end the nomads' raiding. Saudi Arabia offers free seed, housing, and cash bonuses to those who settle, but new wells do even more to draw herdsmen to permanent camps. High-school graduates in Iran's Literacy Corps bring blackboard lessons and health care to villagers, a task carried out by village institutes in Turkey and Egypt. Land reforms divides large estates among some of the landless in Syria, Iraq, Iran, and Egypt. Everywhere ambition quickens; hope can see over the horizon.

Cities: The Magnets

In growning numbers, nomads and villagers stream into towns and cities, joining the age old mix of merchants, landlords, artisans, scholars, clerks, laborers, and servants, Much is familiar. Tribal and religious compatriots, clustering in residental quarters, have connections that often aid the newcomer. Soothing calls to prayer come from great mosques, though villagers still lament that “there is no religion in the towns.” For the fortunate few, universities where scholars once lectured on Moslem theology, science, and law now offer a full range of modern-day subjsets.

Hundreds of open-faced stalls in antique suqs, or bazaars, display supermarket variety. The handcrafted silk of Damascus, the tooled leather of Fez, and the copperware of Nicosia increasingly give way to aluminum pans and plastics from Mainz, Bucharest, and Tokyo, or from local factories.

Though hampered by the scarcity of raw materials, literate workers, and tranind managers, the Middle East looks toward industrialization as an open sesame to progress. In modern factories men weave textiles, process food, assemble autos, and produce chemicls and cement. In Egypt, Iran, and Algeria, imported scrap iron feed giant steel mills, while Turkey's own coal and iron support the nation's heavy industry. Still there are not enough jobs or houses, and shantytowns grow. Industrial technology–the time clocks, the assembly lines, the fragmentated family life–clash with the Middle Easterner's love of personal dealings, hospitality, and bargaining.

In the lands the world remembers for Cleopatra and the Queen of Sheba, women take places in the sun after centuries in the shadow of seclusion. Empress Farah of iran promotes health and educational opportunities. Golda Meir, a onetime trade unionist and Milwaukee school-teacher, is Prime Minister of Israel. Women serve in the parliaments of Iran and Egypt and in the cabinets of Turkey and Afghanistan, They broadcast news on Cairo television, practice psychiatry in Istanbul, program computers in Amman, and design office buldings in Baghdad.

More than 1,300 years ago, Islam raised the status of women, recognizing their rights to property, inheritance, and divorce. A polygamous man was limited to four wives, and he must treat each equally. But Mohammed left men as “protectors over the women,” at the top of the social order. Since a woman's honor mirrored amily's reputation, she was strictly guarded by father, brothers, and husband.

Over the past half century interest in women's rights has grown. Women may vote in most lands. Tunisia has pioneered birth-control clinics. Mothers go to primary school with their children, and tirbal women who cannot read boast of daughters with university degrees. Strict segregation survives in Saudi Arabia, where young women pursue university courses by correspondence or in off-campus buildings. But in Lebanon, israel, Turkey, Morocco, iran, and Iraq more than a third of the college students are women.

After nightfall, a man turns toward the holy city of Mecca and, for the fifth and final time of the day, he kneels. Touching his forehead to the ground, he repeats ritual prayers and professes aloud, “I witness that there is no god but Allah, and that Mohammed is His Apostle.” From West Africa to Indonesia, in classical Arabic–the prescribed language of Islam–some 500 million Moslems re-echo the fervent refrain.

To Moslems, Mohammed, the man of seventh-century Mecca, stands as the greatest and last in the line of prophits that includes Adam, Abraham, and Jesus. Through Mohammed, they believe, God relayed an immutable message, recorded in the Koran, It preaches Islam, submission to God's will, chiefly through five basic pillars of the faith: profession of belief, prayer, almsgiving, fasting and pilgrimage. The Koran also decrees just treatmentfor all men and prohibits such practices as usury, gambling, and wine drinking. Supplemented by the sayings and deeds of Mohammed and by scholarly interpretations, the Koran soon became the basis of law, or Sharia, for the entire community of believers. Religion and politics were inseparable.

When Islam bust across the Middle East, it encountered Jews and Christians–the “People of the Book.” All three faiths shared a vision of one God–a God of justie and mercy–and of the brotherhood of man. Islam offered the stamp of finality… God had spoken for the last time.

The conquered embraced the new faith in growing numbers. But some chose special status. By paying a head tax and living peacefully, a non-Moslem community might keep its place of worship, its law coded, and its property. During the subsequent Ottoman Empire, such groups, or millets, continued to enjoy the same privileges. In Lebanon, to this day, parliamentary seats and high government posts are assigned to religious communities according to their munerical strength. Egypt places no restriction on the rites of its four million Coptic Christians. In small pockets elsewhere, other religions follow distinctive liturgies, among them Zoroastrians in Iran, Greek Orthodox, Eastern-Rite Catholics, and Jacobites in Syria, and Nestorians (Assyrians) in Iraq.

While tolerating non-Moslems, Islan itself divided into a melange of sects. The first rift came over the choice of Mohammed's successor. One faction saw in Mohammed's son-in-law Ali the fulfillment of their longing for an infallible ruler, imam, distinguished by a divine spark. Ali's followers–the Shias–subsequently split into sects such as Iran's Imamis, the Alawites and Ismailis of Syria, and the Zaidis of Yemen (Sana). But most Moslems are Sunni, or orthodox, wholly rejecting and intermediary between the faithful and God. the predominate in most Middle Eastern Moslem lands, while the Shias–now only a tenth of the Moslem World–often focus politican dissent.

“The problem is not how to get money, but how to spend it,” laments Sheik Zayid ibn Sultan al-Nahayan, President of the oil-rich United Arab Emirates. The welcome dilemma struck the Middle East after World War II, as international oil companies discovered and tapped the largest proven reserves anywhere–nearly 70 percent of of the world's total. Some 20 million barrels a day now flow from the region, principally to fuel the engines of Westen Europe and Japan.

United in their negotiations, Middle Eastern governments recently bargained to receive a larger share of the profits. Now they seek a greater role in management. The windfall gives a mighty boost to basic development and armaments and a trump card in diplomacy. Iran builds a strong armed force plus roads and schools. Libya, with 1.7 billion dollars in oil revenues last year alone, improves housing the hospitals. Iraq constructs bridges and roads. Tiny Kuwait, floating on 15 percent of the world's oil, assures every citizen free education, medical care, pensions, and no income tax. Both Kuwait and Libya grant loans to sister Arab states. At desert oil complexes, some 100,000 rural Middle Easterners grasp 20th-century technical skills–and also get a look at Western life-styles.

Black-veiled women line up before a ballot box near Cairo ... Students, agitating for more freedom of speech, stop traffic in Baghdad ... A religious scholar of Damascus presents a petition to Syria's socialist regime denouncing lax morals.

Political consciousness grips the Middle East. Its governments, as varied as its peoples, range from absolute monarchies to republics in the Western mold, such as Turkey and Lebanon.

Traditionalists, viewing religion and state as one, desire strong enforcement of the Islamic code. King Faisal of Saudi Arabia, a member of the ruling Saudi family approved by a consensus of religious scholars, balances traditional and modern forces. A religious cadre enforces the public observance of prayer, temperance, and daytime fasting during the month of Ramadan, while royal decrees spread progressive concepts of commerical and labor relations and social welfare.

But Western ideas, especially nationalism, have shattered the universality of religious rule, Turkey led the break in the 1920s by closing the Islamic lawbooks and creating a secular republic. Elsewhere, secular ideas penetrate in varying degrees. Tunisia, for example, adopted representative government, but declared Islam the state religion. Hereditary monarchs of Afghanistan, Iran, Jordan, and Morocco introduced parliaments and constitutions yet still exercise old prerogatives that circumvent the powers of the legislatures.

Everywhere, hational armes play a major role in politics. Imbued with ideals of reform, young officersof Iraq, Syria, Yemen (Sana), Egypt, Libya, and Algeria have staged coups to promote drastic change. Yet, in response to popular demand, they retain the Islamic family codes governing marriage, divorce, and inheritance.

Israel follows British precedents in its parliamentary democracy, while maintaining rabbinical courts that control marriage and divorce for Jews.

Professing a policy of nonalignment, some Arab states respond to United States support of Israel by accepting massive Soviet aid; armaments, loans, and trade agreements. But atheistic ideology hold scant ppeal for Moslems. Libya, Sudan, and Egypt have cracked down on Communist interference in local politics, and no nation has adopted a Communist governement–a measure of the Middle East's determination to find its own way.

Ebb and Flow of Empires

EARLY CIVILIZATIONS: The Nile Valley and Mesopotamia boasted superb cultural achievements and the world's first cities by 3000 B.C., at a time when Europeans still lived in rude huts. By 1300 B.C.. writing preserved legal codes and beliefs in one God; calendars captured time. Ambitious Persians extended the first modern empire with a common language and coinage, a postal and road system, and religious toleration. Then, in the first major invasion from the West, Alexander the Great took the entire Persian domain and founded some twenty cities, planting Greek culture. His dream of one world–a unified East and West–was realized by the subsequent Roman Empire. Roads, reservoirs, and irrigation works were expanded. Camel caravans and fleets of galleys distributed the papyrus of Egypt, the incense of southern Arabia, the jewels of India,and the silks of China.

BYZANTINE AND SASSANID EMPIRES: As Rome declined, its Emperor Constantine turned to the more prosperous Middle East. In A.D. 324 he founded his New Rome, later called Constantinople, near the Greek colony of Byzantium. Adopting Christianity, he married the new religion to Roman law and Greek culture. Government regulated all aspects of life, from wages to religious rites; heresy was treason. But schisms split off provinces; Egyptina Copts, Syrian Maronites, and Nestorians formed their own churches, which still survive. Border batttles broke out between the Byantines and the Persians, whose civiliation flowered anew under the Sassanid Dynasty. Persian shahs revived ancient Zoroastrianism, with its priests, or magi, and its sacred fires. Despite warefare, trade and cultural exchanges continued. Byzantine and Oriental artistic traditons intermingled.

ARAB EMPIRE: The year one in the Moslem calendar, A.D. 622, marked the move of the Prophet Mohammed from Mecca to Medina, where he established the rule of Islam. Soon Bedouin horsemen exploded out of Arabia, wresting empires from the war-weakened Byzantines and Persians. Islam and the Arabic language unified an empire that reached its zenith in a single century. Mohammed's successors, the Umayyad Dynasty, moved the capital to Damascus, adopting Byzantine culture. Grasping power, the rival Abbasids emulated the Persians and, with Baghdad their capital, brought luxuriant court life and learning to new heights. But the empire fagmented. Rival dynasties sprang up in Cordoba and Cairo. Seljuk Turks usurped power from the Abbasids and then embaraced their culture. Warfare interfered with Christian pilgrims, helping to trigger the Crusades.

THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE expanded from an Anatolian state ruled by the Turkish Ottoman cln to a world power that reched to the gates of Vienna. In 1453 Moslem Turks stormed 1,100-year-old Christian constantinopel. Establishing a sumptuous court there, autocratic sultans imposed an administration so effctive that it won praise from Martin Luther: “theTurk ... rules quite civilly, he preserves peace and punishes criminls.” Christian slaves–converted to Islam, educated, and advanced by merit–rose to govern the realm. Bureaucrats recorded revenue from tirbute, imports, religious minorities, and imperial estates. North African pirates raided European shipping. Gradually, palace intrigues, corruption, and national revolts sapped the empire. Safavid Persians successfully resisted Ottoman conquest. Aided by Europe, Greeks broke away in 1821, followed by other Balkan peoples.

EUROPEAN IMPERIALISM: Western nations, vaulting ahead in technology and military power, extended by their rivalries into the Middle East. Napoleon's bold invasion of Egypt in 1798 set off a race for influence. Britain soon controlled ports on the sea-lane to India. France took most of North Africa and brought in European settlers. Russia annexed the Caucasus and Turkistan. Germany courted the Ottomans, who became her allies in World War I. Britain, in turn, supported the Arab revolt against Ottoman rule, a cause championed by the flamboyant lawrence of Arabia. Britain and Fance agreed secretly to the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire, “the sick man of Europe,” and received Arab lands they coveted as League of Nations mandates. The Arabs–schooled in Western ideals of nationalism–rebelled periodically until the Europeans withdrew after World War II.

MOROCCAN ARAB - Boiling out of Arabia in the seventh century, small armies of fierce horsemen overran the entire southern Meiterranean coastline. they absorbed indigenous Berbers intoarmies that invaded Spain, and established a dazzling court at cordoba. In the 11th century, waves of Bedouin swept across North Africa, intermarrying with Berbers and strengthening the grip of Islam and the Arabic language. Today the majority of Moroccans and other North Africans represent an amalgam of these early groups.

BERBER - Masters of the mountains of North Africa, Berber farmers retain customs–including monogamy–that predate the Arab conquest of their land in the seventh century. Women perpetuate Berber dialects in the home, while men must learn Arabic and French to deal with outsiders. Blue-veiled Berber camelmen–the Tuareg–have controlled major Saharan caravan routes for millenniums.

HARATIN - Oasis dwellers of the Sahara the Haratin descend from black Africans who came north as migrants or slaves. Many cultivate dates and grain for Bedouin and Tuareg landowners, who consider farming beneath their dignity. Dances and songs of the southern Sahara enliven their festivals; gazelle horns and cowrie shells on children's cap symbolize fertility. Haratin profess Islam and speak the Arabic and Berber dialects of their closest neighbors.

Birthplace of the Alphabet

In Mesopotamia and Egypt 5,000 years ago, men first experimented with systems of writing to preserve spoken languages. In hieroglyphic and cuneiform scripts, symbols represented words and syllables. Out of these early models came one of the world's greatest invention–the alphabet.

Phoenician writing–which recorede only consonants–became the grandparent of all modern alphabets. Greeks added symbols for vowels, aninnovation that traveled to the Romans, who develped the Latin alphabet, now used throughout the West.

The ancient script of South Arabia influenced Ethiopic. Aramaic lead to modern Hebrew and Arabic, and–with Greek–influenced Armenian. In the Middle East today, most languages, including Arabic, Persian, and Pashto, are written in Arabic script. Other distinctive writing exist there including Berber, Georgian, Syriac, and Coptic.

Sanctuary shared by three faiths: Jerusalem has been a beacon to Jews since King David transformed a Jebusite town into his capital, Zion, in 1000 B.C. Solomon enlarged the city to the north, and built a temple where the Dome of the Rock now stands. Nearby, Jesus was crucified. Today's walled city, remodeled by Romans, Crusaders, and Ottoman Turks, lay in Jordan from 1948 until 1967, when Israel captured it and consolidated it with the New City to the west.

City open to Moslems only: Mecca was western Arabia's commercial center in the late sixth century; caravaneers on the Yemen-Damascus route rested here and worshiped many gods at the Kaaba, a cube-shaped shrine. Introducing Islam, Mohammed cast out the idols, but kept the Kaaba and the pilgrimage, or hajj, as a once-in-a-lifetime dutry for all believers. Now during the annual week of the hajj, the city grows from 250,000 to more than a million.

|

| Geographical Equivalents |

| Burnu, Burun ... cape, point |

Idehan ... sand dunes |

| Chott ... intermittent salt lake, salt marsh |

'Irq ... sand dunes |

| Daglari ... mountains |

Jabal, Jebel ...mountains, peak range |

| Daryacheh ... lake, marshy lake |

Kuh-e ... mountains, peak, range |

| Dasht ... desert plain |

Oued ... river, valley, watercourse |

| Dawhat ... bay, cove, inlet |

Ras, Ra's ... cape, point |

| Erg ... sand dune region |

Sabkhat, Sebkha ... salt lake or marsh |

| Gebel ... mountain, peak, range |

Sahra ... desert |

| Ghard ... sand dunes |

Sarir ... gravel desert |

| Hamada, Hammadah ... rocky desert |

Shott ... intermittent salt lake, salt marsh |

| Hamun ... depression, lake |

Tall, Tel-l ... hill, mound |

| Hawr ...lake, marsh |

Wadi ... river, valley, watercourse |