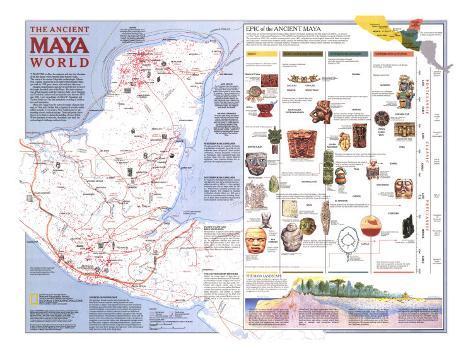

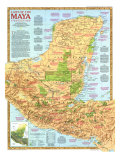

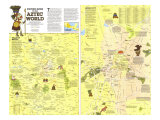

The 1989 Ancient Maya World map features:

• Sites officially recorded by archaelogical agencies

• Routes of the conquistadors

• Information on the Mayan landscape including geology, rainfall, and vegetation

• Sea trade routes, trade routes, sacbe (Maya causeway), and possible portage

• Trade goods including salt, shells, cacao, feathers, pottery, and obsidian

• Information on the eras of Maya history

• Illustrations and information about artifacts

Guatemala, Mexico, Honduras, El Salvador

* Lesson plan idea - have your students update the information and latest disoveries concerning the Mayan civilization; discuss the political, economic, and environmental situations that are current for the region. • maps

“I WANTED to efface the centuries and hear the vibrations of the last human voices beneath these massive vaults...” The voices of the ancient Maya that archaeologist Alberto Ruz Lhuillier yearned for as he entered the fabulous Palenque tomb in 1952 grow clearer with each new discovery.

Spanish conquistadores and clerics were the first to record the jungle-shrouded ruins of the Maya. But their existence was all but forgotten until the explorers John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood surveyed the area between 1839 and 1842. Later expedtions of Alfred P. Maudslay and Teobert Maler saw the first meticulous recording of architecture and monuments.

Maya sites range from the restored remains of great cities such as Tikal and Chichen Itza to clusters of scarecely visible rubble mounds. Caves such as Naj Tunich preserve outstanding artwork and inscriptions. Tools and pottery have shown up in fields or during the building of resort hotels. Where hundreds of sites rose, flourished and died, the archaeological challenge contines today.

SOURCES OF KNOWLEDGE - The talented, literate people who developed the New World's most complex writing system left much for scholars to digest. And Spanish records provide invaluable eyewitness accounts of the 16th-century Maya. Archaelolgists unearth building to reconstruct local cultures; they date and compare artifacts to deduce patterns of trade and influence. Botanists study ancient pollen to detect changes in the climate and environment. Art historians interpret religious icons and the canons of art and architecture. Epigraphists seek to decipher hieroglyphs to recover the history and propaganda through which the Maya elite sought to immortalize themselves. Ethnohistorians study the early documents. Linguists compare Mayan languages and chart their changes through time, while ethnologist study the rich world of the living Maya.

Three terms are used for the general dating of Mya history. Preclsssic applies to the time span from 2000 B.C. to around A.D. 250, Classic to the period between A.D. 250 and 900, and Postclassic from 900 to the Spanish conquest of Mexico in 1521. The colonial rea, 1521-1821, and the modern period, snce 1821, complete the chronolgical framework. Dates recorded in the Long Count–the five-place notation system used by the lowland Maya of the Classic period–have been converted to Gregorian calendar dates by the Goodman-Martinez-Thompson correlation formula, which matches, for example, the Maya date 9.0.0.0.0 with December 11, 435, in the Christian era.

NORTHERN MAYA LOWLANDS - Though paralleling the southern lowlands in settlement and growth, the north did not suffer the same collapse of Classic period civilization. Instead prosperity continued as Postclassic cities expanded trade and received ideas from the central Mexican highlands. Later rivalries divided the region into 16 competing provinces.

SOUTHERN MAYA LOWLANDS - As ingenious farming techniques coaxed rich harvests from these tropical forest–settled as early as 1000 B.C.–the southern lowlands gave rise to large cities by 100 B.C. Within three centuries powerful city-states reigned. The collapse of lowland civilization shortly before A.D. 900 saw a decline in population and building. Pockets of Maya here remained unconquered by the Spanish until as late as 1697.

PACIFIC COAST AND MAYA HIGHLANDS - Monumental sculpture and carved stelae bearing Long count dates and hieroglyphic texts mark the beginning of the highland Maya civilization during the Late Preclassic. Its elaborate calendar was later perfected by astronomers in the Maya lowlands. Early in the Christian era strong influences from central Mexico created a hybrid Maya-Mexican culture here.

THE SOUTHEASTERN FRONTIER - Within the broad band of land that includes western Honduras and El Salvador, ancient Maya culture merged with that of other peoples to the east and south. Preclassic and Classic period sites in the western part of this zone reflect the Maya culture; those farther east show little or no Maya influence. The picture is further clouded by the presence of the Pipil and other groups from central Mexico who occupied much of the area in Postclassic times.

THE MAYA LANDSCAPE

A region of complex geology and vegetaton, the cross section of the maya homeland below cuts across Mesoamerica from the Pacific coast in the south to the Gulf of Mexico in the north. (In the illustration) the vertical dimension has been exaggerated to better show the difference in terrain at this scale. The height of the vegetaton is even more exaggerated to show its variety.

GEOLOGY: A narrow Pacific coastal plain rises abruptly into the Maya highlands–a wide band of mountains and volcanoes subject to frequent earthquakes. Slowly emerging from the sea, a great slab of limestone forms the Maya lowlands of the Yucatan Peninsula, North of Latitude 20º ther are no rivers, but underground water percolates through the porous limestone forming caverns.

LANDSCAPE: The Maya highlanders lived with a mixed blessing: The volcanic eruptions that created rich soil and valued trade items, such as obsidian, also threatened home and fields. In the less fertile lowlands, Maya farmers cleared forests for slash-and-burn agriculture, created raised farm plots in swamps, and sometimes terraced hillsides.

RAINFALL: Subject to tropical deluges, the Maya region receives most of its yearly abundance between June and October. The annual rainfall varies throughout theregion, from as much as 300 centimeters in the southern lowlands to only 25 centimeters in the northwestern part of the Yucantan Peninsula. Hurricanes lash the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean coastlines.

VEGETATOPM: The evergreen forests dominating the highlands give way in the southern lowlands to tropical rain forests of mahaganies, wild figs, and other giants the soar to a 50-meter canopy. Marching north on the Yucatan Peninsula, forests gradually diminish in height. Encroaching development now threatens all areas.

MAYA CODICES - Four Postclassic Maya hieroglyphic books–folidn-screen manuscripts on bask paper thinly coated with lime palster–have survived in arious states of completion. There, probably part of the booty of the Spanish conquest, are among thel ibrary and museum teasures of Dreden, Marid and Pars. the fourth, not in Mexico City, is said to have been found in a cave in Chiaps. All contain ritual almanacs astonomical tables, and images of gods, people, and animals.

THE MAYA CHRONICLES - At various times during the colonial period, traditional versions of Maya history, cosmology, astrology, and medicine were set to paper by local seers and scribes in Yucatec Maya using the Spanish alphabet. These chronicles, collectively called the Books of Chilam Balam for a legendary Maya prophet, contain a wealth of informaton on ancient beliefs, ceremonies, and culture of the northern Maya.