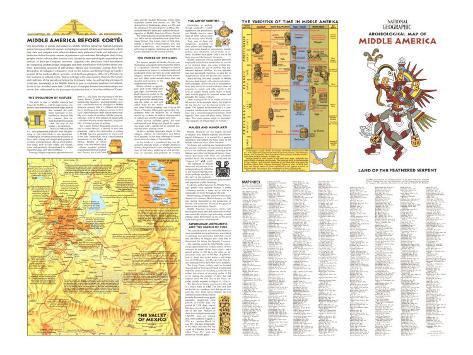

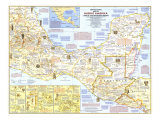

MIDDLE AMERICA BEFORE CORTES

Our knowledge of people and culture in Middle America before the Spanish conquest stems from many different sources. Archeologists unearth artifacts and monuments which they date and compare with others to deduce early patterns of trade and influence. Art historians define the main current of prehistoric style and taste. Ethnologist study living peoples whose cultures often furnish clues valuable in reconstructing the mentalities and motives of their pre-Conquest ancestors. Linguists infer prehistoric tribal movements by comparing modern Indian languages and their distribution with known earlier patterns. Eyewitness accounts of 16th-century Mexico and Guatemala – among them Fray Bernardino de Sahagun's exhaustive work on the Aztecs, and Bishop Diego de Landa's account of the northern Maya – provide vivid firsthand glimpses of the New World in its last moments of cultural purity. Native writings of the same century chronicle the history and traditions of the period just before the Europeans came. As anthropological research continues, knowledge of the Middle American past is constantly modified and refined. So far it has revealed more than 12,000 years of complex human interrelationships and events that culminated in the panorama of splendor that so awed the soldiers of Cortes.

THE EVOLUTION OF CULTURE

Thr story of man in Middle America had begun by 10,000 B.C., with Ice Age hunters who preyed upon mammoth and other large animals that roamed the cool, moist landscape of central Mexico. Around 7000 B.C., warmer, drier climate doomed the animals – and the way of the hunter – to extinction.

Between 7000 and 2000 B.C., man progressed gradually from the gathering of wild plant foods to true agriculture. Archeological evidence shows the evolution to have been a long and complicated process of accident and experiment, during which particular crops, such as corn, beans, and squash, were independently domesticated in widely separated areas after about 6000 B.C.

Farming villages and pottery appeared around 2000 B.C., and mark the beginning of the Pre-classic Period. Typical remains of this time include clay figurines – probably fertility symbols – that herald the rise of religion in Middle America. Around 1000 B.C. Olmecs built that area's first large-scale religious centers in their Gulf Coast homeland; their culture spread rapidly over much of southern Middle America, carrying – with its dark religion of jaguar gods – the New World's earliest calendar, and probably, a limited system of writing.

The Classic Period, beginning around A.D. 100 in central Mexico, a century or two later elsewhere, reflects the culmination of culture in Middle America, particularly in science and in the arts. Teotihuacan, once a small farming community in the Valley of Mexico, became an urban center – the New World's first – whose powerful political and cultural influence reached into Oaxaca, the Gulf Coast area, and the Yucatan Peninsula, where other important centers rose around A.D. 300. The destruction of Teotihuacan, about A.D. 750, and the collapse of the great Zapotec and Maya theocracies some 150 years later, marked the disintegration of Middle America's Classic Period.

The Toltec state rose in central Mexico around A.D. 900 to set the militaristic ideal of the Post-classic Period. The Aztecs, heirs of that ideal, created a blend of ceremonialism, civic an social organizaton, and conquest that was achieving its highest expression as the fleet of Cortes appeared on the eastern horizon.

THE POWER OF THE GODS

The ancient peoples of Middle America saw themselves as insignificant beings at the mercy of a capricious universe. Attempts to reduce the mysteries of nature to understandable and predictable terms lead them to create elaborate religious systems in which gods were numerous and often could assume more than one identity and function in the supernatural hierarchy.

Deities related to agriculture, such as the Maya corn god, ..., consistently occupied important niches in the Middle American pantheons. Most prominent among these was the water, or rain, god called Tlaloc by the Aztecs an other Nahuatl speakers, and Chac by the Maya of Yucatan. Other gods appeared or disappeared from the religious art, or simply moved up or down in rank as characteristics of culture and society change with time.

Ritual activity included games, the most widespread type being one played by opposing teams with a rubber ball in specially constructed stone playing courts.

Sacrifice, another dominant theme of this religion, reached its culmination just before the conquest, in the mass offering of human hearts from the altars of Tenochtitlan.

In the hands of a priesthood that was all-powerful through much of Middle America's history, the persuasive force of religion created most of that area's enduring art and architecture, its calendar, and probably it writing.

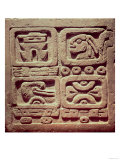

THE ART OF WRITING

Knowledge of writing, though confined to a small segment of the population, sets Middle America apart from all other culture areas of the ancient New World.

Texts vary in form and complexity, according to time, culture, and language, and have been found on monuments, murals, pottery, and ornaments, and in books, or codices, or folded bark paper. Only a few of the latter survived the Spanish Conquest.

Middle American writing systems generally employed symbols that stood either for sounds or for abstract ideas, and some writing progressed toward the use of symbols that represented separate syllables. No true alphabet was ever developed; therefore, no easy key to decipherment exists for present-day scholars.

Maya writing, the most complex in Middle America, deals largely with calendrical matters. Some passages, carved on sets of monuments, have been found to record birthdays, dates of accession to power, and other events in the lives of Classic Period rulers. Many of these texts include glyphs for personal names and probably the names of places.

Aztec wrting made use of simple pictures to tell stories. ... a shield denotes war, the flaming temple, conquest ... two elements together - the head of a cat (tucuani), and a conventionalized hill (tepec). Read together, they form the place name, Tehuantepec. The whole phrase might be translated, “the conquest of Tehuantepec by warfare.”

MAJOR AND MINOR ARTS

Middle American art was largely devoted to religion and, despite regional and chronological differences, it is marked by a general uniformity that reflects the basic unity of the Middle American view of the universe.

Sculpture and painting are characterized by the constant repetition of supernatural themes such as the feathered serpent, grotesque birds, and other mythological figures. Commonly assoicated with these are subsidairy abstract forms that include the scrool and the “stepped fret” motif.

The hallmark of Middle American architecture is its widespread use of platforms or flat-topped stepped pyramids – perhaps symbolic of the tiers of the universe – that formed elevated bases for the great temples and important public buildings.

Under the skilled hands of the Middle American potter – who worked without a wheel – ceramics became a major art as well as a commodity of trade throughout the area.

Metalworking, probably imported from South America via western Mexico around A.D. 800, was mainly channeled to the production of jewelry and ornaments that mark the great art styles of the Postclassic Period.

Middle America's anonymous artists, with the chipped stone axes and other tools of what was essentially a Stone Age technology, created esthetic forms that endure as one of the area's most distinguished achievements.

ASTRONOMY, ARITHMETIC, AND THE MARCH OF TIME

The calendar system, one of Middle America's most remarkable accomplishments, was a blend of astrology and astronomy intimately woven into the fabric of religion and ritual that so dominated life before the Spanish Conquest.

The calendar shared by most Middle American peoples defined the endless motion of their universe by means of two basic cycles – one a sacred period of 260 days, and other an approximate solar year of 365 days. A permutation of these two cycles forms a still larger one of 18,980 days – the 52-year cycle that Aztecs celebrated with the New Fire Ceremony.

The Long Count, widely used by lowland Maya priests of the Classical Period, was the most elaborate method of recording a particular day within this system of recurring cycles. It did so by stating the number of days that had elapsed since the first day of the Maya calendar, usually equated to August 11, 3114 B.C.

The date shown (illustration) was found on the wall of a Maya tomb in Tikal. The bars and dots on the left are numbers: each dot equals one: each bar, five. From top to bottom, the five numbered time period symbols beneath the introductory glyph represent, respectively, nine periods of 144,000 days; one period of 7,200 days; one of 360 days; ten of 20 days; and ten of one day. Products of these five multiplications total 1,303,770 days – an interval that, when added to August 11, 3114 B.C., reaches March 18, A.D. 457 – the date of the tomb. In the Maya calendar, that day – part of a 260-day cycle – was called “Four Oc,” and was shown by the last glyph.